yoga. How they work together can be understood

from the following story:

Once upon a time a couple lived happily together

in a country that had an unjust king. The king

became jealous of their happiness and threw the

man into a prison tower. When his wife came to the

tower at night to comfort him, the man called down

to her that she should return the next night with a

to her that she should return the next night with along silken thread, a strong thread, a cord, a rope, a

beetle, and some honey. Although puzzled by the

request, the wife returned the next evening with all

the items. Her husband then asked her to tie the

silken thread to the beetle and smear honey onto its

antennae. She should then place the beetle on the

tower wall with its head facing upward. Smelling

the honey, the beetle started to climb up the tower

in expectation of finding more of it, dragging the

silken thread as it did so. When it reached the top

of the tower the man took hold of the silken thread

and called down to his wife that she should tie the

strong thread to the other end. Pulling the strong

thread up, he secured it also and instructed her

further to tie the cord to the other end. Once he had

the cord the rest happened quickly. With the rope

attached to the cord he pulled it up, secured one

end of it and, climbing down, escaped to freedom.

The couple are, of course, yogis. The prison tower

represents conditioned existence. The silken thread

symbolizes the purifying of the body through asana.

The strong thread represents pranayama, breath

extension, the cord symbolizes meditation, and the

rope stands for samadhi, the state of pure being.

Once this rope is held, freedom from conditioned

existence is possible.

Patanjali’s eight limbs of yoga relate to Ashtanga

Vinyasa practice thus:

The first limb consists of a set of ethics, which

ensures that the yogi interacts in a harmonious way

with the surrounding community. The ethical precepts

are: not to harm others, to be truthful, not to

steal, to engage in intercourse only with one’s

partner, and to abstain from greed.

The second limb consists of observances, which

ensure that body and mind are not polluted once

they have been purified. Purification in yoga has

nothing to do with puritanism. Rather it refers to the

“stainability” of body and mind. “Stainability” is the

propensity of the body/mind to take on a conditioning

or imprint from the environment. The observances

are physical and mental cleanliness, contentment,

simplicity, study of sacred texts, and acceptance of

the existence of the Supreme Being. The first two

limbs are initially implemented from the outside, and

they form a platform from which practice is undertaken.

Once we are established in yoga they become

our second nature: they will arise naturally.

The third limb is asana. Many obstacles to knowing

one’s true nature are manifested in the body, for

example disease, sluggishness, and dullness. The

body profoundly influences and, if in bad condition,

impinges on the functioning of mind and intellect.

Through the practice of yoga asanas the body is

made “strong and light like the body of a lion,” to

quote Shri K. Pattabhi Jois. Only then will it provide

the ideal vehicle on the path of yoga.

As the Yoga Sutra explains,5 every thought, emotion,

and experience leaves a subconscious imprint

(samskara) in the mind. These imprints determine

who we will be in the future. According to the Brhad

Aranyaka Upanishad, as long as liberation is not

achieved, the soul, like a caterpillar that draws itself

from one blade of grass over to the next, will, by the

force of its impressions in this life, reach out and

draw itself over to a new body in a new life.

This means that the body we have today is nothing

but the accumulation of our past thoughts, emotions,

and actions. In fact our body is the crystallized

history of our past thoughts. This needs to be deeply

understood and contemplated. It means that asana is

the method that releases us from past conditioning,

stored in the body, to arrive in the present moment.

It is to be noted that practicing forcefully will only

superimpose a new layer of subconscious imprints

based on suffering and pain. It will also increase

identification with the body. In yoga, identification

with anything that is impermanent is called

ignorance (avidya).

This may sound rather abstract at first, but all

of us who have seen a loved one die will remember

the profound insight that, once death has set in, the

body looks just like an empty shell left behind. Since

the body is our vehicle and the storehouse of our

past, we want to practice asana to the point where it

serves us well, while releasing and letting go of the

past that is stored in it.

Yoga is the middle path between two extremes. On

the one hand, we can go to the extreme of practicing

fanatically and striving for an ideal while denying

the reality of this present moment. The problem

with this is that we are only ever relating to ourselves

as what we want to become in the future and

not as what we are right now. The other extreme is

advocated by some schools of psychotherapy that

focus on highlighting past traumas. If we do this,

these traumas can increase their grip on us, and we

relate to ourselves as we have in the past, defining

ourselves by the “stuff that’s coming up” and the

“process that we are going through.” Asana is an

invitation to say goodbye to these extremes and

arrive at the truth of the present moment.

How do past emotions, thoughts, and impressions

manifest in the body? Some students of yoga experience

a lot of anger on commencing forward bending.

This is due to past anger having been stored in the

hamstrings. If we consciously let go of the anger, the

emotion will disappear. If not, it will surface in some

other form, possibly as an act of aggression or as a

chronic disease. Other students feel like crying after

intense backbending. Emotional pain is stored in the

chest, where it functions like armor, hardening

around the heart. This armor may be dissolved

in backbending. If we let go of the armor, a feeling

of tremendous relief will result, sometimes

accompanied by crying.

Extreme stiffness can be related to mental rigidity

or the inability to let oneself be transported into

unknown situations. Extreme flexibility, on the other

hand, can be related to the inability to take a position

in life and to set boundaries. In this case, asana

practice needs to be more strength based, to create

a balance and to learn to resist being stretched to

inappropriate places. Asana invites us to acknowledge

the past and let it go. This will in turn bring us

into the present moment and allow us to let go of

limiting concepts such as who we think we are.

The fourth limb is pranayama. Prana is the life

force, also referred to as the inner breath; pranayama

means extension of prana. The yogis discovered that

the pulsating or oscillating of prana happens sim

ultaneously with the movements of the mind

(chitta vrtti). The practice of pranayama is the study

and exercise of one’s breath to a point where it is

appeased and does not agitate the mind.

In the vinyasa system, pranayama is practiced

through applying the Ujjayi breath. By slightly

constricting the glottis, the breath is stretched long.

We learn to let the movement follow the breath,

which eventually leads to the body effortlessly

riding the waves of the breath. At this point it is

not we who move the body, but rather the power

of prana. We become able to breathe into all parts of

the body, which is equivalent to spreading the prana

evenly throughout. This is ayama — the extension

of the breath.

The fifth limb is pratyahara — sense withdrawal.

The Maitri Upanishad says that, if one becomes

preoccupied with sense objects, the mind is fueled,

which will lead to delusion and suffering.6 If, however,

the fuel of the senses is withheld, then, like a

fire that dies down without fuel, the mind becomes

reabsorbed into its source, the heart. “Heart” in

yoga is a metaphor not for emotions but for our

center, which is consciousness or the self.

In Vinyasa Yoga, sense withdrawal is practiced

through drishti — focal point. Instead of looking

around while practicing asana, which leads to the

senses reaching out, we stay internal by turning

our gaze toward prescribed locations. The sense of

hearing is drawn in by listening to the sound of the

breath, which at the same time gives us feedback

about the quality of the asana. By keeping our

attention from reaching out, we develop what tantric

philosophy calls the center (madhya). By developing

the center, the mind is eventually suspended and

the prana, which is a manifestation of the female

aspect of creation, the Goddess or Shakti, ceases to

oscillate. Then the state of divine consciousness

(bhairava) is recognized.7

The sixth limb is dharana — concentration. If you

have tried to meditate on the empty space between

two thoughts, you will know that the mind has the

tendency to attach itself to the next thought arising.

Since all objects have form, and the witnessing

subject — the consciousness — is formless, it tends

to be overlooked by the mind. It takes a great deal

of focus to keep watching consciousness when dis -

tractions are available.

The practice of concentration, then, is a pre -

requisite and preparation for meditation proper. The

training of concentration enables us to stay focused

on whatever object is chosen. First, simple objects

are selected, which in turn prepare us for the

penultimate “object,” formless consciousness, which

is nothing but pure awareness.

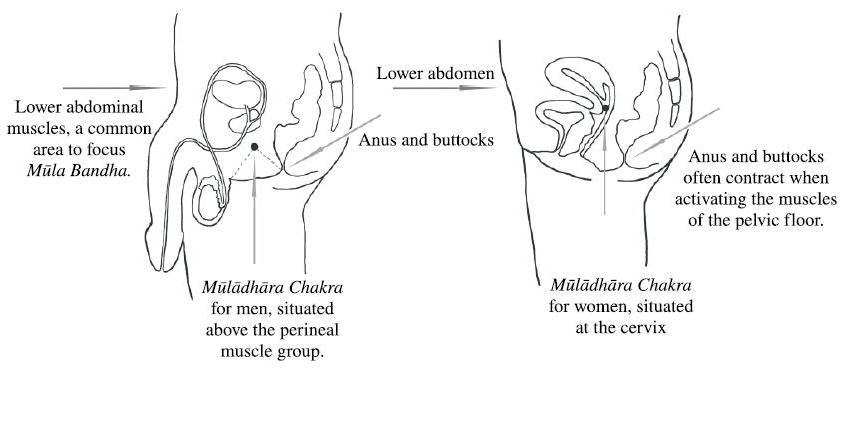

Concentration in Vinyasa Yoga is practiced by

focusing on the bandhas. On an external level the

focus is on Mula and Uddiyana Bandha (pelvic and

lower abdominal locks), but on an internal level it is

on the bonding together of movement, breath, and

awareness (bandha = bonding). To achieve this

bonding, we have to let go of the beta brain-wave

pattern, which normally accompanies concentration.

Instead we need to shift to an alpha pattern, which

enables multiple focus and leads into simultaneous

awareness of everything, or being in this moment,

which is meditation.

The seventh limb is dhyana — meditation.

Meditation means to rest, uninfluenced, between the

extremes of the mind and suddenly just “be” instead

of “becoming.” The difference between this and the

previous limb is that, in concentration, there is a

conscious effort to exclude all thoughts that are not

relevant to our chosen object. In meditation there is

a constant flow of impressions from the object and

of awareness toward the object, without any effort

of the will. Typical objects chosen are the heart lotus,

the inner sound, the breath, the sense-of-I, the

process of perception, and intellect, one’s meditation

deity (ishtadevata) or the Supreme Being.

In Vinyasa Yoga, meditation starts when, rather

than doing the practice, we are being done or moved.

At this point we realize that, since we can watch the

body, we are not the body but a deeper-lying witnessing

entity. The vinyasa practice is the constant

coming and going of postures, the constant change

of form, which we never hold on to. It is itself a

meditation on impermanence. When we come to the

point of realizing that everything we have known so

far — the world, the body, the mind, and the practice

— is subject to constant change, we have arrived

at meditation on intelligence (buddhi).

Meditation does not, however, occur only in

dhyana, but in all stages of the practice. In fact the

Ashtanga Vinyasa system is a movement medi -

tation. First we meditate on the position of the body

in space, which is asana. Then we meditate on the

life force moving the body, which is pranayama.

The next stage is to meditate on the senses through

drishti and listening to the breath, which is pratyahara.

Meditating on the binding together of all

aspects of the practice is concentration (dharana).

The eighth limb, samadhi, is of two kinds —

objective and objectless. Objective samadhi is when

the mind for the first time, like a clear jewel, reflects

faithfully what it is directed at and does not just

produce another simulation of reality.8 In other

words the mind is clarified to an extent that it does

not modify sensory input at all. To experience this,

we have to “de-condition” ourselves to the extent

that we let go of all limiting and negative programs

of the past. Patanjali says, “Memory is purified, as if

emptied of its own form.”9 Then all that can be

known about an object is known.

Objectless samadhi is the highest form of yoga.

It does not depend on an object for its arising but,

rather, the witnessing subject or awareness, which is

our true nature, is revealed. In this samadhi the thought

waves are suspended, which leads to knowing of

that which was always there: consciousness or the

divine self. This final state is beyond achieving,

beyond doing, beyond practicing. It is a state of pure

ecstatic being described by the term kaivalya — a

state in which there is total freedom and independence

from any external stimulation whatsoever.

In the physical disciplines of yoga, samadhi is

reached by suspending the extremes of solar (pingala)

and lunar (ida) mind. This state arises when the inner

breath (prana) enters the central channel (sushumna).

Then truth or deep reality suddenly flashes forth.