The relationship between mental problems and

mental and physical ailments need not be dealt

with in great detail here, for most people fully

accept that almost all illnesses are a result of

some kind of mental disturbance. We merely

want to emphasize this point.

The mind, on a personal level, is in a

continual state of activity at all stratas. Ideally

these processes should occur spontaneously

and naturally, without the slightest hindrance.

In the mind of most people, however, there is

psychological constipation and indigestion,

caused by mental frustrations. This results in

the growth of psychological tumours in the

mind. If these tumours, blocks, frustrations

and mental problems are sufficiently intense

they can result in psychosomatic illnesses and/

or mental illnesses or breakdowns. If the

mental problems are milder, but nevertheless

present, they will manifest in the form of

unhappiness and depression; in fact general

discontent with one's relationship with life and

other people.

It is widely accepted that there are many

illnesses which manifest physically, but which

have psychological causes. In modern language

these are called psychosomatic diseases.

Under this heading are included more obvious

related diseases such as neuritis, but actually

yoga believes that almost all diseases are

caused by mental disturbances. Modern science

is slowly coming around to the same conclusion

by experiment. For example, the general

treatment for cancer in recent times has been

radioactive bombardment of the cancerous

area. Yet at a symposium held at Stanford

University in U.S.A. in 1972, a radiologist had

a far reaching conclusion to convey to medical

science. His revelation caused a stir at the

meeting. He said that he had been using

radiology for many years in the treatment of

cancer patients. Because of the widespread

occurrence of cancer, thousands of patients

besieged him seeking a cure. He of course

could not treat them all at the same time and

so he was forced to make many of them wait

for treatment, often for several weeks. Some

of the people were suffering great pain. The

usual method of combating this pain is

administration of drugs. To reduce this

dependence on drugs, the radiologist recommended

that the patients relieve their pain by

practising relaxation and meditational techniques.

To his great surprise many of these

people showed marked improvement in their

state of health. His conclusion, which he

presented to the members of the symposium,

was obvious: the cause of cancer lies in the

mind, nowhere else. We would also like to add

one point: many people claim that the cause of

cancer, the only cause, is cigarette smoking.

Figures and statistics are presented which

clearly show and prove that the incidence of

cancer is greater with smokers than with nonsmokers.

This may be true, but they miss one

important factor; namely, that people who

smoke are generally those who are very tense.

We are not saying that this is the reason why

they smoke, but that those who smoke have a

tendency to be more tension-ridden. Therefore,

we feel that the cause of cancer is not the

smoking, but mental tension. Smoking may

have some bearing no doubt, but it is a side

issue.

It is a similar case with diabetes. Many people

attribute its cause to the malfunctioning of the

pancreas and perhaps the pituitary gland. No

doubt this is the obvious cause of the lack of

insulin. But what is the reason for the

malfunction in the first place? From contact

with large numbers of diabetics in the ashram,

we feel that the original cause definitely lies in

the mind. Mental disturbance and continual

stress interfere with the harmonious working

of the physical organs causing them to break

down. We know many cases of diabetics who

have learned to relax more in life, through

yoga practices, and their diabetes has

completely disappeared or at least been

reduced.

We could talk about numerous other

illnesses, epilepsy, heart problems and ulcers,

in the same way, but this is not the purpose of

this discussion. We merely want to draw your

attention to the importance that the mind has

on health and lack of health. With removal of

mental problems, incredible changes take place

in the body and state of health. Many miraculous

cures of all types of so-called incurable

diseases can be obtained by relaxing the

deeper realms of the subconscious mind, by

throwing out or coming to terms with one's

inner problems

Páginas

- Pàgina d'inici

- Clases de Ashtanga en Tarragona

- Library

- My practice

- My practice videos

- Ashtanga series

- Ashtanga pranayama sequence

- Pranayama

- Asana

- Yoga meditation

- Mudra&Bandha and Kriya

- Mantra

- Moon days

- Oil bath

- Clips

- Audio/pdf book

- Zen and Vipassana Meditation

- Index

- interviews for Sthira&Bhaga

- textos propios

martes, 28 de enero de 2014

lunes, 27 de enero de 2014

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part2 (2/2)

ls it a spiritual practice he's teaching?

Yeah, i think it's spiritual in the way most people use that word. You

could also say it’s beyond spiritual. If someone has a concept of spiritual-

ity, this is much more interesting than anything they could imagine. But

it's definitely a totally spiritual practice. However, if someone comes to it

and has no interest in what they believe spirituality to be, if they just take

up the practice for improving their health or fixing some biomechanical

problem in the body, it'll prove effective but it will also put them in touch

with their core feelings. And just by touching those core feelings they

will start inquiring into what is real. They'll start to ask: "Why am I suf-

fering all the time?" “What is true?" And so they've come to the right

place. And so yoga in a sense is like a fountain. People will go to it, for

many different reasons but because they've gone to the source they start

to get a taste for it, and they might not really understand why they like it

but they'll keep coming back to the source and eventually they'll just

jump right back in.

It is spiritual in the sense that the Atman, the soul, is revealed, but at the

same time there is a methodology as well, so is it somehow a fusion of those

two things?

Exactly. If we say that what is of most interest to the open mind, to the

open heart, is beyond expression, beyond words, also therefore beyond

technique. our first reaction is “I won't do anything." But the fascinating

thing about practice is that what is manifesting as the body and the mind

is composed of strings and strings of techniques, and so yoga is actually

the art of using techniques with incredible skill and through that one

naturally arrives at a place where there is no technique anymore but free-

dom. This is one of the major themes of the Bhagavad Gita, one of the

extremely illusive themes, that the truth is ultimately formless because it

generates all forms. How can it be approached? How can you realize it?

lt’s actually through seeing forms with an open mind and allowing the

body and the mind to complete their natural tendencies to complete

their forms. and in that you release form.

So you have to see all the forms that your mind wants to manifest to actually

see behind them, mul that goes for all the different asanas as well.

Yes, each one is sacred, each one is like a mandala, or in the Hindu tra-

dition they use the word "yantra," which is a sacred diagram. Yantras have

very distinct forms, so a yoga asana has a very distinct outer form and a

very distinct internal form. and if you are able to go into it, in sometimes

excruciating detail and intensity, and you see it as sacred, if you are sim-

ply able to observe it without reducing it to some concept or theory, then

you are free from that form. The very heart of the yantra or mandala is

you. Then another form comes which happens to be the next pose in the

series, and eventually you are able to see all of these as an expression of

the same internal principle. lt's just that at certain points we get con-

fused and we're not able to see it as sacred, as spiritual.

Has Guruji described to you diflerent mental forms that relate to the differ-

ent asanas?

No, he hasn't. just practice. What he has clone is he's given me a lot of

things to study, books to read. hoping that I will be fascinated and extract

information from them.

Why is there such a strong emphasis on asana practice in this system? What

is the function of going back to the same place daily?

The practice is like a mirror. We go to the mirror every morning to tidy

ourselves up before going out into the world, and the practice is like a

mirror for what's in your heart and what's in your mind. If you are able to

approach the practice from an internal space, it's always new. The same

old pose is always fascinating because you are using it as an object of

meditation rather than as a means to get something. And that way you

are able to practice and practice and practice—perhaps forever.

What is the attitude one needs to get that experience?

I think the key to ashtanga practice is bhakti. which is devotion or love.

The eight limbs are accessories to that heart. Bhakti is probably the clos-

est thing to what yoga is. And so guru bhukti, which is a direct relation-

ship or love for the teacher. is one aspect of bhakti that is extremely

helpful.

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part1 (1/3)

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part2 (2/3)

Yeah, i think it's spiritual in the way most people use that word. You

could also say it’s beyond spiritual. If someone has a concept of spiritual-

ity, this is much more interesting than anything they could imagine. But

it's definitely a totally spiritual practice. However, if someone comes to it

and has no interest in what they believe spirituality to be, if they just take

up the practice for improving their health or fixing some biomechanical

problem in the body, it'll prove effective but it will also put them in touch

with their core feelings. And just by touching those core feelings they

will start inquiring into what is real. They'll start to ask: "Why am I suf-

fering all the time?" “What is true?" And so they've come to the right

place. And so yoga in a sense is like a fountain. People will go to it, for

many different reasons but because they've gone to the source they start

to get a taste for it, and they might not really understand why they like it

but they'll keep coming back to the source and eventually they'll just

jump right back in.

It is spiritual in the sense that the Atman, the soul, is revealed, but at the

same time there is a methodology as well, so is it somehow a fusion of those

two things?

Exactly. If we say that what is of most interest to the open mind, to the

open heart, is beyond expression, beyond words, also therefore beyond

technique. our first reaction is “I won't do anything." But the fascinating

thing about practice is that what is manifesting as the body and the mind

is composed of strings and strings of techniques, and so yoga is actually

the art of using techniques with incredible skill and through that one

naturally arrives at a place where there is no technique anymore but free-

dom. This is one of the major themes of the Bhagavad Gita, one of the

extremely illusive themes, that the truth is ultimately formless because it

generates all forms. How can it be approached? How can you realize it?

lt’s actually through seeing forms with an open mind and allowing the

body and the mind to complete their natural tendencies to complete

their forms. and in that you release form.

So you have to see all the forms that your mind wants to manifest to actually

see behind them, mul that goes for all the different asanas as well.

Yes, each one is sacred, each one is like a mandala, or in the Hindu tra-

dition they use the word "yantra," which is a sacred diagram. Yantras have

very distinct forms, so a yoga asana has a very distinct outer form and a

very distinct internal form. and if you are able to go into it, in sometimes

excruciating detail and intensity, and you see it as sacred, if you are sim-

ply able to observe it without reducing it to some concept or theory, then

you are free from that form. The very heart of the yantra or mandala is

you. Then another form comes which happens to be the next pose in the

series, and eventually you are able to see all of these as an expression of

the same internal principle. lt's just that at certain points we get con-

fused and we're not able to see it as sacred, as spiritual.

Has Guruji described to you diflerent mental forms that relate to the differ-

ent asanas?

No, he hasn't. just practice. What he has clone is he's given me a lot of

things to study, books to read. hoping that I will be fascinated and extract

information from them.

Why is there such a strong emphasis on asana practice in this system? What

is the function of going back to the same place daily?

The practice is like a mirror. We go to the mirror every morning to tidy

ourselves up before going out into the world, and the practice is like a

mirror for what's in your heart and what's in your mind. If you are able to

approach the practice from an internal space, it's always new. The same

old pose is always fascinating because you are using it as an object of

meditation rather than as a means to get something. And that way you

are able to practice and practice and practice—perhaps forever.

What is the attitude one needs to get that experience?

I think the key to ashtanga practice is bhakti. which is devotion or love.

The eight limbs are accessories to that heart. Bhakti is probably the clos-

est thing to what yoga is. And so guru bhukti, which is a direct relation-

ship or love for the teacher. is one aspect of bhakti that is extremely

helpful.

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part1 (1/3)

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part2 (2/3)

lunes, 20 de enero de 2014

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part2 (2/3)

|

| Guruji and Richard Freeman |

It would be part of any yoga teaching. The question is: Does the system

work. or does the collection of systems and methodology work? And in

many cases, in many schools of yoga, not a lot is happening. Yoga tradi-

tionally has been passed down from teacher to student over thousands of

years. and often the lineages are broken, so it is like a wire that is broken

and no current flows through it, so the actual internal teaching doesn't

get transmitted.

Do you know how far back this lineage goes beyond Krishnmnacharya's

teacher? Do we know anything about Rama Mohan Brahmachari's teacher?

No, we don't. Of course, Guruji has a family lineage which is the lineage

of Shankaracharya. And he is constantly making reference to Shankara-

charya. to teachers in the Shankaracharya lineage, and he has much in-

volvement in that, and his yoga gum, Sri Krishnamacharya, also has his

yoga guru and his family lineage. It's a complex thing to study.

|

| Shankaracharya |

How important is a guru when practicing yoga, and how does Guruji perform that function of separating the light from the darkness?

The guru is practically the key to the whole system. I suppose in theory,

if one were extremely intelligent and extremely lucky and extremely kind,

you could learn yoga from a book and you could do very well and get very far. But with a teacher, you develop a relationship. and something right at

the heart of that relationship carries the essence of the practice, and so

the various techniques that you might learn, even the various philoso-

phies you might leam, are placed in an immediate context by the guru.

That context is simply one of complete, open relationship, complete

presence. It's a great thing. So if there's a great teacher around, take ad-

vantage of it! If there's no teacher around, practice anyway.

How would you characterize Guruji's teaching method?

When I first met Guruji, he reminded me very much of a Zen Buddhist

teacher in that he used very few words in his classes. The words he

would use were like koans, they were puzzling, at least to most of the

students. And often, he was just trying to wake you up with what he was

doing. It wasn't so much the content of what he was saying. He would

sometimes try to distract you or to place you in a kind of double bind

where you might just laugh and let your breath flow and all of a sudden

find yourself doing a posture that you had feared two minutes before.

l remember doing backbends in Mysore with Guruji. We were just

standing and arching back and grabbing our knees which is, if you think

about it, very scary at times. I was all set to do it with my arms crossed

and he looked at my shorts which were soaking wet and cotton and he

said, “Oh, nice material!" just as I was starting to drop back and made me

completely forget my preconceptions. And the backbend was no problem

at all.

When there is fear going into a pose, does he have a technique to take you

deeper, beyond your body's apparent natural capacity?

l think what he does is he makes you drop your presuppositions, your

preconceptions about your body and therefore about your limitations.

Oftentimes you'll approach him and say, “Oh Guruji, this muscle is hurt-

ing" or "This bone has this problem." And he'll just look at you and say,

“What muscle?" In other words, he is inviting you again to look with a

completely fresh mind to see if there is anything really there. And by

dropping the concept you have around a sensation or feeling, you release

them. Many times the concept is the limiting factor. He's a master at

that: seeing if there is some fear or some attachment. And usually, in a

very kind, sometimes gentle, sometimes abrupt way, he'll get you to re-

frame a situation.

ls he imparting that skill to Sharath?

l think naturally he is. That's just the way he relates to people, and so

Sharath is bound to pick it up I think.

|

| Guruji and Sharath |

Guruji immediately present, which is an intense way to practice. So

Sharath experiences sometimes a lot of pain, sometimes his own fear,

and so he is very sympathetic with the students, very compassionate, be-

cause he has learned to be compassionate with himself when he prac-

tices. Guruji is also that way, but he doesn't do asana practice anymore

and so he just takes you right into it.

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part1 (1/3)

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part2 (3/3)

jueves, 16 de enero de 2014

Pada Bandha by Mark Stephens

With twenty-six bones that form twenty-five joints, twenty muscles, and a variety of tendons and ligaments, the feet are certainly complex. This complexity is related to their role, which is to support the entire body with a dynamic foundation that allows us to stand, walk, run, and have stability and mobility in life. In yoga they are the principal foundation for all the standing poses and active in all inversions and arm balances, most back-bends and forward bends, and many twists and hip openers. Meanwhile they are also subjected to almost constant stress, ironically one of the greatest stresses today coming from a simple tool originally designed to protect them: shoes. Giving close attention to our feet—getting them strong, flexible, balanced, aligned, rooted, and resilient—is a basic starting point for building or guiding practically any yoga practice, including seated meditation.

In order to support the weight of the body, the tarsal and metatarsal bones are constructed into a series of arches. The familiar medial arch is one of two longitudinal arches (the other is called the lateral arch). Due to its height and the large number of small joints between its component parts, the medial arch is relatively more elastic than the other arches, gaining additional support from the tibialis posterior and peroneus longus muscles from above. The lateral arch possesses a special locking mechanism, allowing much more limited movement. In addition to the longitudinal arches, there are a series of transverse arches. At the posterior part of the metatarsals and the anterior part of the tarsus these arches are complete, but in the middle of the tarsus they present more the characters of half-domes, the concavities of which are directed inferiorly and medially, so that when the inner edges of the feet are placed together and the feet firmly rooted down, a complete tarsal dome is formed. When this action is combined with the awakening of the longitudinal arches, we create pada bandha, which is a key to stability in all standing poses (and a key source of mula bandha).

However, the feet do not stand alone, even in Tadasana, nor do they independently support movement. Activation of the feet begins in the legs as we run lines of energy from the top of our femur bones down through our feet. This creates a “rebounding effect.” Imagine the feeling of being heavier when riding up in an elevator, or lighter when riding down. The pressure of the elevator floor up against your feet not only makes you feel heavier, it has the effect of causing the muscles in your legs to engage more strongly. Similarly, when you intentionally root down from the tops of your thighbones down into your feet, the muscles in your calves and thighs engage. This not only creates the upward pull on the arches of pada bandha (primarily from the stirrup-like effect of activating the tibialis posterior and peroneus longusmuscles) but creates expansion through the joints and a sense of being more firmly grounded yet resilient in your feet while longer and lighter up through your body.

martes, 14 de enero de 2014

lunes, 13 de enero de 2014

domingo, 12 de enero de 2014

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part1 (1/3)

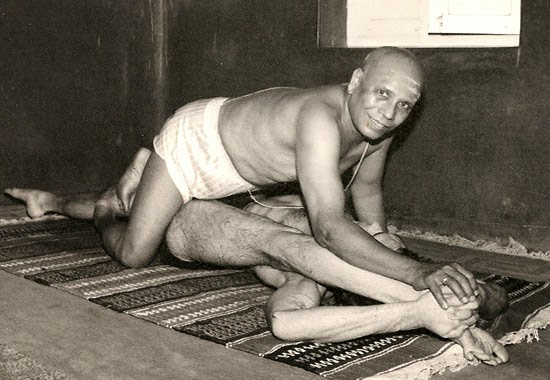

Richard Freeman met Guruji after an extensive period of spiritual un-

dertakings which began in I967 and included living as a monk in India,

becoming an avid yoga practitioner, and devoting himself to philosophi-

cal studies. He has been instrumental in spreading aslmmga yoga in lhe

West.

way to Mysore?

I don’t remember when I first heard about it, but I knew of its existence

for a number of years. First, through the work of Desikachar—the concept

of vinyasa, that things occur in sequences and that you can practice yoga

asana in sequences. And then I learned that Pattabhi jois was going to

come to the United States and lead a workshop at the Feathered Pipe

Ranch in Montana. and so I signed up right away. When I met him I was

enthralled by his radiance and his kindness. We almost had an instant

connection. And fortunately; we were in a place that was isolated. There

were two classes every day and hours of time in between to talk, and it was

an exciting experience. I was swept off my Feet by Guruji when I met him.

What was your first impression of him?

I was impressed by his smile, his radiance, his overall sweetness. I found

him extremely accessible. He was willing to tell me anything I wanted to

know, and that was actually rare in teachers. I was swept off my feet.

I 've often heard Guruji say he teaches real or original Patanjali yoga.

What was your experience of him as a teacher of true yoga?

When someone says they teach Patanjali yoga, the eight limbs of yoga,

they are implying that not only do they teach asana and pranayama but

also samadhi and all of the stages of meditation and then the release, or

the self-realization through samadhi. My experience of Guruji is that this

is what his interest is. Practically his only interest in life is to fulfill the

whole yoga system. His emphasis is, of course, on intense asana practice

at first. but through that asana practice with the vinyasa methodology he

is also teaching the fundamentals of pranayama and meditation. And

much later on in his system, these particular parts are separated out and

refined. But in a sense he is teaching the eight limbs initially through

asana practice, and when one picks up the thread inside, we find that the

other limbs are very easy to practice. And so he is saying the first four

limbs of yoga—yaama, niyama, asana. and pranayama—are very difficult,

but if you are grottnded in them, the intemal limbs are easy and occur

spontaneously. naturally.

Does he actually teach them themselves or are they just incorporated in

the asana practice?

He teaches them on a one-to-one basis when he wants to. If someone is

really interested, dying for it, he teaches the internal limbs. Practically,

you have to be experiencing them already so that it's easy to teach. If

someone is burning with desire. then they are so close that the teacher

doesn't have much to do except say yes, that's it.

Is samadhi far off for us?

Samadhi is very close. according to my understanding. Practicing yoga,

you gradually develop the ability to observe what is happening in the

present moment, and when you observe very closely what is actually occurring, then that is samadhi. And what is occurring is very close to us.

Usually we are looking at some other place rather than at what is actually

happening. So yoga asana and pranayama allow the attention to focus on

what is actually happening. Present feelings, present sensations, and the present pattem of the mind become sacred, they become the object of

meditation. So many people try to practice meditation but are trying to

practice by observing what isn't present. They are trying to look behind

this, they are trying to look anyplace, let me see anything but this. But

when you practice asanas enough, when you practice pranayama, the very

sensation that you are having presently is what is sacred. You stop looking

elsewhere and samadhi starts to occur.

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part2 (2/3)

From the book "Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students" Richard Freeman excerpts part2 (3/3)

miércoles, 8 de enero de 2014

Sharing the Mat: The Synergy of Yoga & Buddhism- Richard Freeman

Richard Freeman: My primary practice is ashtanga yoga, that includes yoga asana and pranayama breath practice, and then I practice with mantra and chants. I practice probably two to three hours a day, and as part of that I do sitting meditation for about ten to fifteen minutes. I do buddhist retreats throughout the year. Sometimes I teach yoga asana practice at the retreats while a buddhist co-presenter teaches meditation.

So I am probably weighted on the side of the hatha yoga tradition, with a sprinkling of the buddhadharma to

|

| Richard Freeman |

Richard Freeman: People who simply do sitting meditation can develop a kind of a crust around themselves, in which they avoid temptation, avoid feeling, and avoid the grounded-ness of the body. on the other hand, while hatha yoga practice is extremely helpful, it runs the danger of people not practicing it mindfully. So body and mind practices are kind of an antidote for each other. Historically, this has been expressed as the joining of raja yoga, which would be considered contemplative practice, and hatha yoga, which is primarily energy work. When the two come together there’s success in practice.

Richard Freeman: What is the difference between the body and the mind, ultimately? One of the axioms of yoga is that the mind, or chitta, and the internal breath of energy, prana, are really two ends of the same stick. So all of our sensations, feelings, and thought forms actually correspond to fluctuations of our prana - See more at:

Richard Freeman: Today in the West we are being overwhelmed by the variety of lineages and practices we can choose from. Most of these are imported practices, which means we don’t have particular obligations in terms of our family or culture to favor one over the other. We are in the position to look at all of them and ask, What does it all mean? Can we legitimately borrow from one and then borrow from another? Can we synthesize them? At what point is that appropriate? That makes it very challenging for practitioners, yet I think it’s a fantastic opportunity to really get to the bottom of the practice. On the other hand, we always run the risk of becoming watered-down eclectics, using the fact that there are alternative practices to avoid going deeply into any one of them. If a practice is legitimate, at a certain point it’s going to make us face things as they are. We’re going to have to face the fact of impermanence and death, and that’s very difficult. Often people will bail out at that moment and jump to a different tradition. Then they’ll stay with that one until the same crisis arises, and they’ll jump to a different school. that’s why we need a lot of communication with a good teacher, so that they can check whether we’re avoiding something or actually facing reality. We should never just assume that what we’re doing is the right thing. –

Richard Freeman: We see everything from utterly materialistic yoga practice, in which people are looking purely to enhance the beauty of their body, all the way across the spectrum to yoga practice as a form of inquiry into reality. it’s my perception that the big fad of yoga is probably weighted a little bit toward the materialistic side, where people are simply looking for some kind of pleasure that works. But i’m also sympathetic to that type of practice. I think people find that unless they follow the practice to its end, it doesn’t really work as a permanent source of pleasure. So at least people are getting a good start and going to the right source. Then they have an opportunity to discover what the practice is really about. I’m optimistic about the overall state of affairs in the yoga world

Richard Freeman: On a very practical level, Buddhist communities are well-organized to conduct sitting retreats. In the more traditional yoga lineages, one learns the meditation and then goes off and practices in retreat, but not often with a large group of people. What the Buddhist communities do so well is conduct practical meditation sessions in a way that’s very inclusive. The simplicity of the mindfulness-awareness approach is that it doesn’t require a theological commitment. It doesn’t require a secret mantra; it just puts you face-to-face with your breath and your mind, allowing people to get started right away with the meditation practice. I think that’s wonderful. So here in boulder, which is a great Buddhist center, I try to take full advantage of the local resources, and I encourage all my yoga students to meditate.

Richard Freeman: I think one of the advantages of “importing” hatha yoga into the Buddhist community is that the current state of yoga asana technology arising out of india is very good. It’s just a very wonderful practice. I know the tibetan system usually requires years of sitting practice before students are allowed to study the tantric yoga practices. A lot of those practices are not taught to large numbers of people, whereas millions of people practice hatha yoga.

If they’re shopping around for hatha yoga, I think Buddhists should look outside of the buddhist community for the latest updates, the most efficient information about how to do it. Conversely, the non-buddhist community—i don’t want to use the word “hindu” because that’s too confusing a label—should look to the buddhist community to see how to present the essence of the Vedanta in a very non-sectarian, compassionate way.

Richard Freeman: I don’t think there’s going to be a single synthesis arising in which all of the yoga schools and all of the buddhist schools understand their essential interpenetration and become one big, monolithic, happy family. But I have a feeling that communication is really opening up, and that people are no longer afraid to consider other traditions, to consider that maybe other schools have a least a couple of good points to make. This more open attitude is going to generate a lot more practice and insight, because in the past people have not wanted to even look at a book from another tradition. But the world is getting smaller as we communicate more and more, and we may find that what we think are fundamental differences aren’t that solid and important. I think there’s going to be a lot of life coming out of this exchange.

martes, 7 de enero de 2014

Two Roads Diverged- Richard Freeman

The first yoga teacher Richard Freeman ever met was a Zen Buddhist at the Chicago Zen Center in 1968. “He taught only one posture,” Freeman says, “sitting zazen. But that was yoga.” Since then, Freeman has spent nearly nine years in Asia studying various traditions which he incorporates into the ashtanga practice taught to him by his principle teacher, K. Pattabhi Jois. Freeman’s background includes Zen and Vipassana meditation, Bhakti, traditional hatha and Iyengar yogas, and Sufism. He lives in Boulder, Colorado where he is the director of the Yoga Workshop.

How are yoga and Buddhism similar?

If you look at something like the Yoga Sutra, you can see the Buddhism woven into it. A lot of the terminology is Mahayana terminology. The schools are similar enough, but their cultures are different—so they either infuriate or inspire one another.

The Indian yoga that is popular now in the States is not really representative of yoga. Most yogis in India will do a couple of postures, get that alignment and quit when they’re twenty-five because they hurt their necks doing it.

Then what do they do?

Then they do their meditation and pranayama. If you go all over India, that’s mostly what you find. In terms of the brilliant practice of asanas that you find in North America, that’s just one thread coming through Krishnmacharya and his students.

You teach ashtanga mainly because ...

It’s just what I wound up doing! The term “ashtanga” isn’t just referring to the vigorous methodology of Pattabhi Jois; it refers to the classical eight limbs, not unlike the eightfold path of the Buddha. Within the yoga schools, ashtanga implies a type of practice that is oriented towards insight for the purpose of liberation—not the cultivation of anything else.

Is it true that people are turning to Buddhism in order to gain insight into the three marks of existence, because those teachings aren’t available through the study of yoga?

People are turning to Buddhism for that because of the dubious quality of the instruction that is available. This is part of the social phenomenon of yoga. So many people have gone to India for teacher training, and have gotten a watered-down version for mass consumption. It’s easy and profitable.

Most of the yogic scriptures start out talking about suffering, impermanence and the basic problem of ignorance. If you were from another planet, you would say that yoga’s the same as Buddhism.

The thing with Indian yogis—and this is not universally true but it is true with some—they’re very reluctant to really teach stuff that is chewy and heavy. They have this cultural snobbery, particularly if they’re Brahmins. They figure that these students can't understand it anyway—maybe they will in their next life. Or maybe if they’re good boys and girls, they will in this life.

One of the traditional Hindu teachings is that most people aren’t really interested in the truth. So you give them some religious form that will do them good, and you keep them in their place. Then, at a certain point, they’ll inquire.

So there’s not the urgency for Indian yogis to save all beings. Eventually they want to save all beings. But they figure they have lots of time.

If you look at what’s happening in Western yoga, people are pretty much caught up in the idea of being super-healthy and full of bliss, grasping at pleasurable states of consciousness.

Does that disturb you, knowing what you know?

Oh yeah. So this is the way my contemplation usually goes: at least they’re a little bit interested in the subject. At least they’re getting started in it. If their teachers have some integrity, people will start learning more.

People come to yoga for all kinds of reasons. Mostly they want something. But the same could be said of Buddhism: people want peace of mind or something. Their desire still tends to be egocentric. But if they’ve come to a good source, they’ll start to get more than they asked for, more than they bargained for. And that’s the hope with this huge wave of popularity of yoga—that there’ll be a significant percentage of people who really take to it and really inquire into its roots. I remain optimistic.

How are yoga and Buddhism similar?

|

| Richard Freeman |

If you look at something like the Yoga Sutra, you can see the Buddhism woven into it. A lot of the terminology is Mahayana terminology. The schools are similar enough, but their cultures are different—so they either infuriate or inspire one another.

The Indian yoga that is popular now in the States is not really representative of yoga. Most yogis in India will do a couple of postures, get that alignment and quit when they’re twenty-five because they hurt their necks doing it.

Then what do they do?

Then they do their meditation and pranayama. If you go all over India, that’s mostly what you find. In terms of the brilliant practice of asanas that you find in North America, that’s just one thread coming through Krishnmacharya and his students.

You teach ashtanga mainly because ...

It’s just what I wound up doing! The term “ashtanga” isn’t just referring to the vigorous methodology of Pattabhi Jois; it refers to the classical eight limbs, not unlike the eightfold path of the Buddha. Within the yoga schools, ashtanga implies a type of practice that is oriented towards insight for the purpose of liberation—not the cultivation of anything else.

Is it true that people are turning to Buddhism in order to gain insight into the three marks of existence, because those teachings aren’t available through the study of yoga?

People are turning to Buddhism for that because of the dubious quality of the instruction that is available. This is part of the social phenomenon of yoga. So many people have gone to India for teacher training, and have gotten a watered-down version for mass consumption. It’s easy and profitable.

Most of the yogic scriptures start out talking about suffering, impermanence and the basic problem of ignorance. If you were from another planet, you would say that yoga’s the same as Buddhism.

The thing with Indian yogis—and this is not universally true but it is true with some—they’re very reluctant to really teach stuff that is chewy and heavy. They have this cultural snobbery, particularly if they’re Brahmins. They figure that these students can't understand it anyway—maybe they will in their next life. Or maybe if they’re good boys and girls, they will in this life.

One of the traditional Hindu teachings is that most people aren’t really interested in the truth. So you give them some religious form that will do them good, and you keep them in their place. Then, at a certain point, they’ll inquire.

So there’s not the urgency for Indian yogis to save all beings. Eventually they want to save all beings. But they figure they have lots of time.

If you look at what’s happening in Western yoga, people are pretty much caught up in the idea of being super-healthy and full of bliss, grasping at pleasurable states of consciousness.

Does that disturb you, knowing what you know?

Oh yeah. So this is the way my contemplation usually goes: at least they’re a little bit interested in the subject. At least they’re getting started in it. If their teachers have some integrity, people will start learning more.

People come to yoga for all kinds of reasons. Mostly they want something. But the same could be said of Buddhism: people want peace of mind or something. Their desire still tends to be egocentric. But if they’ve come to a good source, they’ll start to get more than they asked for, more than they bargained for. And that’s the hope with this huge wave of popularity of yoga—that there’ll be a significant percentage of people who really take to it and really inquire into its roots. I remain optimistic.

lunes, 6 de enero de 2014

miércoles, 1 de enero de 2014

Varaha Upanishad quotes

A wise

man who has understood the course of nadis and vayus

should,

after keeping his neck and body erect with his mouth

closed,

contemplate immovably upon Turyaka (Atma) at the

tip

of his nose, in the centre of his heart and in the middle of

bindu,

and

should see, with a tranquil mind through the

(mental)

eyes, the nectar flowing from there. Having closed

the

anus and drawn up the vayu and caused it to rise through

(the repetition of) pranava (Om).

He

should try to go up by the union of Prana and Apana.

This

most important yoga brightens up in the body the path of

siddhis.

As a dam across the water serves as an obstacle to the

floods,

so it should ever be known by the yogins that the chhaya

of

the body is (to jiva). This bandha is said of all nadis.

Through

the grace of this bandha, the Devata (goddess) becomes

visible.

This bandha of four feet serves as a check to the three

paths.

This brightens up the path through which the siddhas

obtained

(their siddhis). If with Prana is made to rise up soon

Udana,

this bandha checking all nadis goes up. This is called

Samputayoga

or Mulabandha. Through the practising of this

yoga,

the three bandhas are mastered. By practising day and

night

intermittingly or at any convenient time, the vayu will

come

under his control. With the control of vayu, agni (the

gastric

fire) in the body will increase daily. With the increase

of

agni, food, etc., will be easily digested. Should food be

properly

digested, there is increase of rasa (essence of food).

With

the daily increase of rasa, there is the increase of dhatus

(spiritual

substances). With the increase of dhatus, there is the

increase

of wisdom in the body. Thus all the sins collected

together during many crores of births are

burnt up.

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)