Es como si alguien cocina como un acto de amor o lo hace solamente para preparar algo para alimentarse, es la intención lo que define el acto.

Páginas

- Pàgina d'inici

- Clases de Ashtanga en Tarragona

- Library

- My practice

- My practice videos

- Ashtanga series

- Ashtanga pranayama sequence

- Pranayama

- Asana

- Yoga meditation

- Mudra&Bandha and Kriya

- Mantra

- Moon days

- Oil bath

- Clips

- Audio/pdf book

- Zen and Vipassana Meditation

- Index

- interviews for Sthira&Bhaga

- textos propios

sábado, 15 de noviembre de 2014

La práctica espiritual

Hay persona que identifican una práctica espiritual con un ambiente exótico y extraño a la gente, cuando esa parte interna de nuestro ser nos acompaña des del nacimiento y lo que revela es una visión mucho más enfocada y definida de la realidad que rodea nuestra vida cotidiana. No es algo que se pueda practicar una o dos veces por semana o pueda pretenderse aprender, porque es algo innato en el alma humana que eventualmente se puede manifestar en las persona que están cultivando ese aspecto. No es una cuestión de buscar algo insólito y confuso, sino más bien entrar en un eje de extrema realidad y comprensión. Por lo cual la practica espiritual no se puede definir por el ambiente externo y el decorado, sino por la intención con la que uno mismo en su interior la desarrolla.

Es como si alguien cocina como un acto de amor o lo hace solamente para preparar algo para alimentarse, es la intención lo que define el acto.

Es como si alguien cocina como un acto de amor o lo hace solamente para preparar algo para alimentarse, es la intención lo que define el acto.

jueves, 13 de noviembre de 2014

Chakras: Energy Vortices from the book prana and pranayama 3/3

Vishuddhi chakra

Vishuddhi is the purification centre and is known as the fountain of youth. According to tantric philosophy, amrita or the nectar of life falls down from bindu into this chakra, generating vitality, health and longevity. In the yogic texts it is stated that with the awakening of this centre all diseased

states can be reversed, and even an old person can become young once again.

When vishuddhi is activated cool, sweet drops of nectar drip down into the throat, causing a feeling of blissful intoxication. The ability to neutralize poison, both internally and externally, is also associated with vishuddhi. At this level all the poisonous and negative experiences of life can be absorbed and transformed into a state of bliss.

Vishuddhi is associated with vijnanamaya kosha and initiates higher mental development. It is the centre for receiving sound vibrations and acts like a transistor radio, allowing one to tune into the thoughts of others, whether close by or far away. When vishuddhi is purified, the sense of hearing becomes very sharp, not only through the ears, but through the mind.

Vishuddhi is located behind the throat pit in the spine and is associated with the thyroid gland. The element is ether or akasha. By meditating on vishuddhi, the mind becomes free of thought, pure and empty, like space. Vishuddhi is seen as a violet lotus with sixteen petals. Its bija mantra is Ham.

Ajna chakra

Ajna literally means 'command' and is the monitoring centre, also known as the guru chakra. It is the point of confluence where the three main nadis, energy channels: ida, pingala and sushumna, merge into one stream of consciousness and flow up to sahasrara. During deep meditation, when all the senses have been withdrawn and one enters into the dimension of shoonya, or void, guru or the higher consciousness guides the aspirant from ajna to sahasrara by issuing commands through this centre.

Ajna is the centre of mind and represents a higher level of awareness. It is also known as the eye of Shiva, the third eye or the eye of intuition, which gazes inward rather than outward. It is often called divya chakshu, the divine eye, or jnana chakshu, the eye of wisdom, because the spiritual aspirant receives revelation and insight into the underlying nature of

existence through this centre. Ajna is the doorway through which one enters the psychic or astral dimension. When this centre is developed one acquires psychic powers. Direct mind-to-mind communication takes place at this level.

At ajna lies the rudra granthi, the knot of Shiva. This knot is symbolic of attachment to the psychic personality and to the siddhis which accompany the awakening of ajna chakra. It effectively blocks one's spiritual evolution until attach-ment to psychic phenomena is overcome and the knot is freed. The trigger point for ajna is located at the eyebrow centre. It is known as bhrumadhya and is an important focal point for the practice of meditation, concentration and visualization.

The development of ajna is very important for success in pranic science. Prana can never be experienced in the form of light unless ajna is developed to some extent. The vision of light is usually seen first at ajna or bhrumadhya, or in chidakasha, the space of consciousness, which is directly associated with ajna. In the practice of prana vidya, ajna acts as the control centre for the distribution of prana. If the vision of light at ajna is well developed, one will have no difficulty in visualizing the raising of prana and its movement throughout the body. Otherwise, the imagination must be used until the actual experience develops.

Ajna is associated with vijnanamaya kosha. It is located at the top of the spinal cord in the mid-brain and corresponds to the pineal gland. The tattwa or element is mind. This is the point where the mind changes from gross to subde, from outward to inward. Ajna is represented by a silver lotus with two petals. The bija mantra is Om.

Bindu

Bindu means 'point'. It is the point of creation where oneness first divides into multiplicity, the ultimate point from which all things manifest and into which all things return. Within bindu is contained the evolutionary potential for the myriad objects of the universe, the blueprint for creation. Bindu is

the gateway to shoonya. It is located at the top back of the head, at the point where Hindu brahmins keep a tuft of hair called shikha.

Bindu is represented by a crescent moon and a drop of white nectar. The tantric texts describe a small depression or pit within the higher centres of the brain which contains a minute secretion of fluid. In the centre of that tiny secretion is a small point of elevation, like an island in the middle of a lake. In the psycho-physiological framework, this tiny point is considered to be bindu.

The moon at bindu produces amrita, the life-giving nectar, and the sun at manipura consumes it. This means that during the course of life, the drop of nectar produced at bindu falls down to manipura, where it is consumed by the fire element. Due to this process one suffers from the three ailments of vyadhi, disease, jara, old age; and mrityu, death. Yoga and tantra employ techniques by which one is able to reverse this process, so that the amrita is retained at vishuddhi, or sent back up from manipura to vishuddhi, and then to bindu. In this way perfected yogis have experienced immortality.

The first manifestation of creation was nada or sound, and bindu is also the point where the original nada emanates. Bindu is associated with anandamaya kosha. When bindu is awakened, the transcendental sound of Om is heard. Bindu is very important in prana vidya and in many higher yogas.

Sahasrara

Sahasrara is the seat of supreme consciousness, located at the crown of the head. Actually it is not a psychic centre at all, because it is beyond the realm of the psyche. Sahasrara is the totality, the absolute, the highest point of human evolu-tion, which results from the merging of cosmic consciousness with cosmic prana. The experience of cosmic prana is the aim of the science of prana. Once mahaprana is experienced, one no longer needs to practise techniques. Transmission of energy will take place spontaneously with a thought, gesture, word or look.

Sahasrara is the master key that controls the awakening of all the chakras from mooladhara to ajna. The chakras are only switches; their potential power lies in sahasrara. When the kundalini shakti reaches sahasrara, self-realization or samadhi dawns. At this point, individual consciousness dies and universal consciousness is born. Sahasrara is infinite in dimension, like a huge radiant dome. It is visualized as a thousand-petalled lotus, unfolding from the crown of the head in all directions into eternity. Sahasrara is associated with anandamaya kosha.

Vishuddhi is the purification centre and is known as the fountain of youth. According to tantric philosophy, amrita or the nectar of life falls down from bindu into this chakra, generating vitality, health and longevity. In the yogic texts it is stated that with the awakening of this centre all diseased

states can be reversed, and even an old person can become young once again.

When vishuddhi is activated cool, sweet drops of nectar drip down into the throat, causing a feeling of blissful intoxication. The ability to neutralize poison, both internally and externally, is also associated with vishuddhi. At this level all the poisonous and negative experiences of life can be absorbed and transformed into a state of bliss.

Vishuddhi is associated with vijnanamaya kosha and initiates higher mental development. It is the centre for receiving sound vibrations and acts like a transistor radio, allowing one to tune into the thoughts of others, whether close by or far away. When vishuddhi is purified, the sense of hearing becomes very sharp, not only through the ears, but through the mind.

Vishuddhi is located behind the throat pit in the spine and is associated with the thyroid gland. The element is ether or akasha. By meditating on vishuddhi, the mind becomes free of thought, pure and empty, like space. Vishuddhi is seen as a violet lotus with sixteen petals. Its bija mantra is Ham.

Ajna chakra

Ajna literally means 'command' and is the monitoring centre, also known as the guru chakra. It is the point of confluence where the three main nadis, energy channels: ida, pingala and sushumna, merge into one stream of consciousness and flow up to sahasrara. During deep meditation, when all the senses have been withdrawn and one enters into the dimension of shoonya, or void, guru or the higher consciousness guides the aspirant from ajna to sahasrara by issuing commands through this centre.

Ajna is the centre of mind and represents a higher level of awareness. It is also known as the eye of Shiva, the third eye or the eye of intuition, which gazes inward rather than outward. It is often called divya chakshu, the divine eye, or jnana chakshu, the eye of wisdom, because the spiritual aspirant receives revelation and insight into the underlying nature of

existence through this centre. Ajna is the doorway through which one enters the psychic or astral dimension. When this centre is developed one acquires psychic powers. Direct mind-to-mind communication takes place at this level.

At ajna lies the rudra granthi, the knot of Shiva. This knot is symbolic of attachment to the psychic personality and to the siddhis which accompany the awakening of ajna chakra. It effectively blocks one's spiritual evolution until attach-ment to psychic phenomena is overcome and the knot is freed. The trigger point for ajna is located at the eyebrow centre. It is known as bhrumadhya and is an important focal point for the practice of meditation, concentration and visualization.

The development of ajna is very important for success in pranic science. Prana can never be experienced in the form of light unless ajna is developed to some extent. The vision of light is usually seen first at ajna or bhrumadhya, or in chidakasha, the space of consciousness, which is directly associated with ajna. In the practice of prana vidya, ajna acts as the control centre for the distribution of prana. If the vision of light at ajna is well developed, one will have no difficulty in visualizing the raising of prana and its movement throughout the body. Otherwise, the imagination must be used until the actual experience develops.

Ajna is associated with vijnanamaya kosha. It is located at the top of the spinal cord in the mid-brain and corresponds to the pineal gland. The tattwa or element is mind. This is the point where the mind changes from gross to subde, from outward to inward. Ajna is represented by a silver lotus with two petals. The bija mantra is Om.

Bindu

Bindu means 'point'. It is the point of creation where oneness first divides into multiplicity, the ultimate point from which all things manifest and into which all things return. Within bindu is contained the evolutionary potential for the myriad objects of the universe, the blueprint for creation. Bindu is

the gateway to shoonya. It is located at the top back of the head, at the point where Hindu brahmins keep a tuft of hair called shikha.

Bindu is represented by a crescent moon and a drop of white nectar. The tantric texts describe a small depression or pit within the higher centres of the brain which contains a minute secretion of fluid. In the centre of that tiny secretion is a small point of elevation, like an island in the middle of a lake. In the psycho-physiological framework, this tiny point is considered to be bindu.

The moon at bindu produces amrita, the life-giving nectar, and the sun at manipura consumes it. This means that during the course of life, the drop of nectar produced at bindu falls down to manipura, where it is consumed by the fire element. Due to this process one suffers from the three ailments of vyadhi, disease, jara, old age; and mrityu, death. Yoga and tantra employ techniques by which one is able to reverse this process, so that the amrita is retained at vishuddhi, or sent back up from manipura to vishuddhi, and then to bindu. In this way perfected yogis have experienced immortality.

The first manifestation of creation was nada or sound, and bindu is also the point where the original nada emanates. Bindu is associated with anandamaya kosha. When bindu is awakened, the transcendental sound of Om is heard. Bindu is very important in prana vidya and in many higher yogas.

Sahasrara

Sahasrara is the seat of supreme consciousness, located at the crown of the head. Actually it is not a psychic centre at all, because it is beyond the realm of the psyche. Sahasrara is the totality, the absolute, the highest point of human evolu-tion, which results from the merging of cosmic consciousness with cosmic prana. The experience of cosmic prana is the aim of the science of prana. Once mahaprana is experienced, one no longer needs to practise techniques. Transmission of energy will take place spontaneously with a thought, gesture, word or look.

Sahasrara is the master key that controls the awakening of all the chakras from mooladhara to ajna. The chakras are only switches; their potential power lies in sahasrara. When the kundalini shakti reaches sahasrara, self-realization or samadhi dawns. At this point, individual consciousness dies and universal consciousness is born. Sahasrara is infinite in dimension, like a huge radiant dome. It is visualized as a thousand-petalled lotus, unfolding from the crown of the head in all directions into eternity. Sahasrara is associated with anandamaya kosha.

viernes, 7 de noviembre de 2014

Chakras: Energy Vortices from the book prana and pranayama 2/3

Swadhisthana chakra

Swadhisthana means 'one's own abode'. It is located at the coccyx, very near to mooladhara, and is also responsible for the awakening of prana shakti. This centre is the storehouse of all the latent samskaras and impressions, which are considered to be the substrata of individual existence. Therefore, it forms a karmic block, making it difficult for the awakened prana to pass through this area.

In psychological terms, swadhisthana is associated with the subconscious mind and is responsible for drowsiness and sleep. It is also related with the reproductive organs and the sense of taste. The desire for pleasure, especially in the form of food and sex, increases when this centre is activated. These desires can become an obstacle to the awakening of prana at this level. In order to pass through this centre one needs to develop willpower.

In relation to the three gunas, or qualities of nature, mooladhara and swadhisthana are predominantly influenced by tamas or lethargy, dullness and ignorance. Swadhisthana is associated with pranamaya kosha and the water element. It is represented by a lotus flower with six vermilion petals. The bija mantra for this centre is Vam.

Manipura chakra

Manipura literally means 'the city of jewels'. Located behind the navel in the spine, its development is very important for success in the pranic science, as it is the storehouse of prana. This centre is associated with heat, vitality, dynamism, generation and preservation. Manipura is often compared with the dazzling orb of the sun, without which there would be no life. As the sun radiates light and energy, so manipura radiates and distributes pranic energy throughout the body, regulating and fuelling life's processes.

Manipura is predominantly influenced by rajas - activity, dynamism, strength and will. This centre is associated with pranamaya kosha and its element is fire. It is represented by a bright yellow lotus with ten petals. Its bija mantra is Ram.

Anahata chakra

Anahata means 'unstruck' or 'unbeaten'. It is the seat of anahad nada, the cosmic sound, which is experienced only in the highest state of meditation. This sound is unstruck, because it is not caused by any external form of friction nor can it be heard by the ears, mind or psyche. It is transcen-dental sound, which can only be perceived by the pure consciousness.

Anahata is the heart centre and is responsible for the awakening of refined emotions. The person with a developed anahata is generally very sensitive to the feelings of others. This centre relates to the sense of touch and its awakening bestows the power to heal others either by touch or by radiating energy. Many people who perform miraculous healing do so through the agency of anahata.

The heart centre is the seat of divine love. It is here that emotion is channelled into devotion. Vishnu granthi, the second psychic knot, representing the bondage of emotional attachment, is located here. When this knot is opened, one becomes free of all selfish, egoistic and emotional attachment, and attains mental and emotional control, equilibrium and peace.

Anahata is associated with manomaya kosha, the mind and emotions. At this level one becomes free of fate and takes control of one's destiny. Hence, the symbol of kalpataru, the wish-fulfilling tree, is also found at this centre. When this tree starts to fructify, whatever one thinks or wishes for comes true. Anahata is located behind the heart in the spine. Its element is air and it is represented by a blue lotus with twelve petals. The bija mantra is Yam.

Swadhisthana means 'one's own abode'. It is located at the coccyx, very near to mooladhara, and is also responsible for the awakening of prana shakti. This centre is the storehouse of all the latent samskaras and impressions, which are considered to be the substrata of individual existence. Therefore, it forms a karmic block, making it difficult for the awakened prana to pass through this area.

In psychological terms, swadhisthana is associated with the subconscious mind and is responsible for drowsiness and sleep. It is also related with the reproductive organs and the sense of taste. The desire for pleasure, especially in the form of food and sex, increases when this centre is activated. These desires can become an obstacle to the awakening of prana at this level. In order to pass through this centre one needs to develop willpower.

In relation to the three gunas, or qualities of nature, mooladhara and swadhisthana are predominantly influenced by tamas or lethargy, dullness and ignorance. Swadhisthana is associated with pranamaya kosha and the water element. It is represented by a lotus flower with six vermilion petals. The bija mantra for this centre is Vam.

Manipura chakra

Manipura literally means 'the city of jewels'. Located behind the navel in the spine, its development is very important for success in the pranic science, as it is the storehouse of prana. This centre is associated with heat, vitality, dynamism, generation and preservation. Manipura is often compared with the dazzling orb of the sun, without which there would be no life. As the sun radiates light and energy, so manipura radiates and distributes pranic energy throughout the body, regulating and fuelling life's processes.

Manipura is predominantly influenced by rajas - activity, dynamism, strength and will. This centre is associated with pranamaya kosha and its element is fire. It is represented by a bright yellow lotus with ten petals. Its bija mantra is Ram.

Anahata chakra

Anahata means 'unstruck' or 'unbeaten'. It is the seat of anahad nada, the cosmic sound, which is experienced only in the highest state of meditation. This sound is unstruck, because it is not caused by any external form of friction nor can it be heard by the ears, mind or psyche. It is transcen-dental sound, which can only be perceived by the pure consciousness.

Anahata is the heart centre and is responsible for the awakening of refined emotions. The person with a developed anahata is generally very sensitive to the feelings of others. This centre relates to the sense of touch and its awakening bestows the power to heal others either by touch or by radiating energy. Many people who perform miraculous healing do so through the agency of anahata.

The heart centre is the seat of divine love. It is here that emotion is channelled into devotion. Vishnu granthi, the second psychic knot, representing the bondage of emotional attachment, is located here. When this knot is opened, one becomes free of all selfish, egoistic and emotional attachment, and attains mental and emotional control, equilibrium and peace.

Anahata is associated with manomaya kosha, the mind and emotions. At this level one becomes free of fate and takes control of one's destiny. Hence, the symbol of kalpataru, the wish-fulfilling tree, is also found at this centre. When this tree starts to fructify, whatever one thinks or wishes for comes true. Anahata is located behind the heart in the spine. Its element is air and it is represented by a blue lotus with twelve petals. The bija mantra is Yam.

lunes, 27 de octubre de 2014

Chakras: Energy Vortices from the book prana and pranayama 1/3

Mooladhara chakra

Mooladhara is the root chakra and the seat of primal energy, kundalini shakti. In philosophical terms the concept of mooladhara is understood as moola prakriti, the transcendental basis of physical nature. All the objects and forms in this universe must have some basis from which they evolve and to which they return after dissolution. This basis is called moola prakriti, the original source of all evolution. Mooladhara, as moola prakriti, is therefore responsible for everything that manifests in the world of name and form.

In pranic science, mooladhara is the generating station for prana. The awakening of prana starts from mooladhara and ascends the spinal cord via the pingala nadi. Pingala is merely the channel; the energy comes from mooladhara. This centre is also the direct switch for awakening ajna chakra. Without the awakening of prana in mooladhara, there can be no corresponding awakening in ajna. Hence, the relationship between mooladhara and ajna is very important. Mooladhara is the generator and ajna is the distributor.

The location of mooladhara in men is at the perineum, midway between the genital organ and the anus, and about two centimetres inside. In women, it is located at the posterior side of the cervix, midway between the vagina and the uterus. Mooladhara is also the location of brahma granthi, the knot of Brahma. As long as this knot remains intact, the energy located in this area is blocked. Prana shakti awakens the moment this knot is undone. Infinite energy and spiritual experience emanate from mooladhara.

Mooladhara is associated with annamaya kosha and the earth element. In psychological terms mooladhara is

associated with the unconscious mind where the most primitive and deep-rooted instincts and fears lie. It is therefore the gateway to hell as well as to heaven; to the lower as well as the higher life.

Mooladhara chakra may be seen in a state of meditation as a deep red lotus flower with four petals. The red petals are seen in meditation because of electrical discharges, which emit light particles in this region. The pattern of the four-petalled lotus is formed due to the relative proximity of the discharges. Thus the chakras are also known as lotuses. Each chakra has a different number of petals, which indicate the level of pranic intensity in that particular region. The bija mantra, or master key, to mooladhara is Lam.

Swadhisthana chakra

Swadhisthana means 'one's own abode'. It is located at the coccyx, very near to mooladhara, and is also responsible for the awakening of prana shakti. This centre is the storehouse of all the latent samskaras and impressions, which are considered to be the substrata of individual existence. Therefore, it forms a karmic block, making it difficult for the awakened prana to pass through this area.

In psychological terms, swadhisthana is associated with the subconscious mind and is responsible for drowsiness and sleep. It is also related with the reproductive organs and the sense of taste. The desire for pleasure, especially in the form of food and sex, increases when this centre is activated. These desires can become an obstacle to the awakening of prana at this level. In order to pass through this centre one needs to develop willpower.

In relation to the three gunas, or qualities of nature, mooladhara and swadhisthana are predominantly influenced by tamas or lethargy, dullness and ignorance. Swadhisthana is associated with pranamaya kosha and the water element. It is represented by a lotus flower with six vermilion petals. The bija mantra for this centre is Vam.

Manipura chakra

Manipura literally means 'the city of jewels'. Located behind the navel in the spine, its development is very important for success in the pranic science, as it is the storehouse of prana. This centre is associated with heat, vitality, dynamism, generation and preservation. Manipura is often compared with the dazzling orb of the sun, without which there would be no life. As the sun radiates light and energy, so manipura radiates and distributes pranic energy throughout the body, regulating and fuelling life's processes.

Manipura is predominantly influenced by rajas - activity, dynamism, strength and will. This centre is associated with pranamaya kosha and its element is fire. It is represented by a bright yellow lotus with ten petals. Its bija mantra is Ram.

Mooladhara is the root chakra and the seat of primal energy, kundalini shakti. In philosophical terms the concept of mooladhara is understood as moola prakriti, the transcendental basis of physical nature. All the objects and forms in this universe must have some basis from which they evolve and to which they return after dissolution. This basis is called moola prakriti, the original source of all evolution. Mooladhara, as moola prakriti, is therefore responsible for everything that manifests in the world of name and form.

In pranic science, mooladhara is the generating station for prana. The awakening of prana starts from mooladhara and ascends the spinal cord via the pingala nadi. Pingala is merely the channel; the energy comes from mooladhara. This centre is also the direct switch for awakening ajna chakra. Without the awakening of prana in mooladhara, there can be no corresponding awakening in ajna. Hence, the relationship between mooladhara and ajna is very important. Mooladhara is the generator and ajna is the distributor.

The location of mooladhara in men is at the perineum, midway between the genital organ and the anus, and about two centimetres inside. In women, it is located at the posterior side of the cervix, midway between the vagina and the uterus. Mooladhara is also the location of brahma granthi, the knot of Brahma. As long as this knot remains intact, the energy located in this area is blocked. Prana shakti awakens the moment this knot is undone. Infinite energy and spiritual experience emanate from mooladhara.

Mooladhara is associated with annamaya kosha and the earth element. In psychological terms mooladhara is

associated with the unconscious mind where the most primitive and deep-rooted instincts and fears lie. It is therefore the gateway to hell as well as to heaven; to the lower as well as the higher life.

Mooladhara chakra may be seen in a state of meditation as a deep red lotus flower with four petals. The red petals are seen in meditation because of electrical discharges, which emit light particles in this region. The pattern of the four-petalled lotus is formed due to the relative proximity of the discharges. Thus the chakras are also known as lotuses. Each chakra has a different number of petals, which indicate the level of pranic intensity in that particular region. The bija mantra, or master key, to mooladhara is Lam.

Swadhisthana chakra

Swadhisthana means 'one's own abode'. It is located at the coccyx, very near to mooladhara, and is also responsible for the awakening of prana shakti. This centre is the storehouse of all the latent samskaras and impressions, which are considered to be the substrata of individual existence. Therefore, it forms a karmic block, making it difficult for the awakened prana to pass through this area.

In psychological terms, swadhisthana is associated with the subconscious mind and is responsible for drowsiness and sleep. It is also related with the reproductive organs and the sense of taste. The desire for pleasure, especially in the form of food and sex, increases when this centre is activated. These desires can become an obstacle to the awakening of prana at this level. In order to pass through this centre one needs to develop willpower.

In relation to the three gunas, or qualities of nature, mooladhara and swadhisthana are predominantly influenced by tamas or lethargy, dullness and ignorance. Swadhisthana is associated with pranamaya kosha and the water element. It is represented by a lotus flower with six vermilion petals. The bija mantra for this centre is Vam.

Manipura chakra

Manipura literally means 'the city of jewels'. Located behind the navel in the spine, its development is very important for success in the pranic science, as it is the storehouse of prana. This centre is associated with heat, vitality, dynamism, generation and preservation. Manipura is often compared with the dazzling orb of the sun, without which there would be no life. As the sun radiates light and energy, so manipura radiates and distributes pranic energy throughout the body, regulating and fuelling life's processes.

Manipura is predominantly influenced by rajas - activity, dynamism, strength and will. This centre is associated with pranamaya kosha and its element is fire. It is represented by a bright yellow lotus with ten petals. Its bija mantra is Ram.

jueves, 9 de octubre de 2014

lunes, 29 de septiembre de 2014

Pancha Kosha: Vital Sheaths from the book prana and pranayama

According to yoga, a human being is capable of experi-encing five dimensions of existence, which are called pancha kosha or five sheaths. These are the five spheres in which a human being lives at any given moment and they range from gross to subtle. The pancha kosha are: i) annamaya kosha, ii) pranamaya kosha, iii) manomaya kosha, iv) vijnanamaya kosha and v) anandamaya kosha.

The first sheath or level of experience is the physical body, or annamaya kosha. The word anna means 'food' and maya 'comprised of'. This is the gross level of existence and is referred to as the food sheath due to its dependence on food, water and air. This sheath is also dependent on prana. While it is possible to live without food for up to six weeks, water for six days, and air for six minutes, life ceases immediately the moment prana is withdrawn from it.

The second sheath is pranamaya kosha, the energy field of an individual. The level of experience here is more subtle than the physical body, which it pervades and supports. This sheath is supported in turn by the subtler koshas. Together, the physical and pranic bodies constitute the basic human structure, which is referred to as atmapuri, city of the soul. They form the vessel for the experience of the higher bodies.

The pranamaya kosha is the basis for the practices of pranayama and prana vidya. It is also described as the pranic,

astral and etheric counterpart of the physical body. It has almost the same shape and dimensions as its flesh and blood vehicle, although it is capable of expansion and contraction. It has been said in the Taittiriya Upanishad (Brahmandavalli:2):

Verily, besides this physical body, which is made of the essence of the food, there is another, inner self comprised of vital energy by which this physical self is filled. Just as the fleshly body is in the form of a person, accordingly this vital self is in the shape of a person.

Clairvoyants see the pranic body as a coloured, luminous cloud or aura around the body, radiating from within the physical body, like the sun flaring from behind the eclipsing moon. Researchers working with a Kirlian high voltage apparatus have obtained similar effects on film. The pranic body is subtler than the physical body and takes longer to disintegrate. This is why the energy field of an amputated limb can be felt for quite some time. As demonstrated in experiments with Kirlian photography, this matrix of energy also allows a damaged part to assume its original shape when healed.

The third sheath is manomaya kosha, the mental dimension. The level of experience is the conscious mind, which holds I he two grosser koshas, annamaya and pranamaya, together as an integrated whole. It is the bridge between the outer and inner worlds, conveying the experiences and sensations of the external world to the intuitive body, and the influences of the causal and intuitive bodies to the gross body.

The fourth sheath is vijnanamaya kosha, the psychic level of experience, which relates to the subconscious and un-conscious mind. This sphere pervades manomaya kosha, but is subtler than it. Vijnanamaya kosha is the link between (he individual and universal mind. Inner knowledge comes

21

astral and etheric counterpart of the physical body. It has almost the same shape and dimensions as its flesh and blood vehicle, although it is capable of expansion and contraction. It has been said in the Taittiriya Upanishad (Brahmandavalli:2):

to the conscious mind from this level. When this sheath is awakened, one begins to experience life at an intuitive level, to see the underlying reality behind outer appearances. This leads to wisdom.

The fifth sheath is anandamaya kosha, the level of bliss and beatitude. This is the causal or transcendental body, the abode of the most subtle prana.

The first sheath or level of experience is the physical body, or annamaya kosha. The word anna means 'food' and maya 'comprised of'. This is the gross level of existence and is referred to as the food sheath due to its dependence on food, water and air. This sheath is also dependent on prana. While it is possible to live without food for up to six weeks, water for six days, and air for six minutes, life ceases immediately the moment prana is withdrawn from it.

The second sheath is pranamaya kosha, the energy field of an individual. The level of experience here is more subtle than the physical body, which it pervades and supports. This sheath is supported in turn by the subtler koshas. Together, the physical and pranic bodies constitute the basic human structure, which is referred to as atmapuri, city of the soul. They form the vessel for the experience of the higher bodies.

The pranamaya kosha is the basis for the practices of pranayama and prana vidya. It is also described as the pranic,

astral and etheric counterpart of the physical body. It has almost the same shape and dimensions as its flesh and blood vehicle, although it is capable of expansion and contraction. It has been said in the Taittiriya Upanishad (Brahmandavalli:2):

Verily, besides this physical body, which is made of the essence of the food, there is another, inner self comprised of vital energy by which this physical self is filled. Just as the fleshly body is in the form of a person, accordingly this vital self is in the shape of a person.

Clairvoyants see the pranic body as a coloured, luminous cloud or aura around the body, radiating from within the physical body, like the sun flaring from behind the eclipsing moon. Researchers working with a Kirlian high voltage apparatus have obtained similar effects on film. The pranic body is subtler than the physical body and takes longer to disintegrate. This is why the energy field of an amputated limb can be felt for quite some time. As demonstrated in experiments with Kirlian photography, this matrix of energy also allows a damaged part to assume its original shape when healed.

The third sheath is manomaya kosha, the mental dimension. The level of experience is the conscious mind, which holds I he two grosser koshas, annamaya and pranamaya, together as an integrated whole. It is the bridge between the outer and inner worlds, conveying the experiences and sensations of the external world to the intuitive body, and the influences of the causal and intuitive bodies to the gross body.

The fourth sheath is vijnanamaya kosha, the psychic level of experience, which relates to the subconscious and un-conscious mind. This sphere pervades manomaya kosha, but is subtler than it. Vijnanamaya kosha is the link between (he individual and universal mind. Inner knowledge comes

21

astral and etheric counterpart of the physical body. It has almost the same shape and dimensions as its flesh and blood vehicle, although it is capable of expansion and contraction. It has been said in the Taittiriya Upanishad (Brahmandavalli:2):

to the conscious mind from this level. When this sheath is awakened, one begins to experience life at an intuitive level, to see the underlying reality behind outer appearances. This leads to wisdom.

The fifth sheath is anandamaya kosha, the level of bliss and beatitude. This is the causal or transcendental body, the abode of the most subtle prana.

miércoles, 17 de septiembre de 2014

martes, 2 de septiembre de 2014

sábado, 23 de agosto de 2014

BKS Iyengar ligth on life quote

What most people want is the same. Most people simply want

physical and mental health, understanding and wisdom, and peace and

freedom. Often our means of pursuing these basic human needs come

apart at the seams, as we are pulled by the different and often competing

demands of human life. Yoga, as it was understood by its sages,

is designed to satisfy all these human needs in a comprehensive, seamless

whole. Its goal is nothing less than to attain the integrity of oneness-

oneness with ourselves and as a consequence oneness with all

that lies beyond ourselves. We become the harmonious microcosm in

the universal macrocosm. Oneness, what I often call integration, is the

foundation for wholeness, inner peace, and ultimate freedom.

lunes, 11 de agosto de 2014

Yoga Sutras, Patanjali. Chapter 4: Kaivalya Pāda

janma auṣadhi mantra tapaḥ samādhijāḥ siddhayaḥ

The mystic skills are produced

through taking birth in particular species,

or by taking drugs, or by reciting special sounds,

or by physical bodily austerities or

by the continuous effortless linkage of the attention

to a higher concentration force, object or person.

jātyantara pariṇāmaḥ prakṛtyāpūrāt

The transformation from one category to another

is by the saturation of the subtle material nature.

nimittaṁ aprayojakaṁ prakṛtīnāṁ

varaṇabhedaḥ tu tataḥ kṣetrikavat

The motivating force of the subtle material energy

is not used except for the disintegration of impediments,

hence it is compared to a farmer.

nirmāṇacittāni asmitāmātrāt

The formation of regions within the mento-emotional energy,

arises only from the sense of identity

which is developed in relation to material nature.

pravṛtti bhede prayojakaṁ cittam ekam anekeṣām

The one mento-emotional energy

is that which is very much used

in numberless different dispersals of energy.

tatra dhyānajam anāśayam

In that case, only subtle activities

which are produced from the effortless linkage of the attention

to a higher reality are without harmful emotions.

karma aśukla akṛṣnaṁ yoginaḥ trividham itareṣām

The cultural activity of the yogis

is neither rewarding nor penalizing,

but others have three types of such action.

tataḥ tadvipāka anuguṇānām

eva abhivyaktiḥ vāsanānām

Subsequently from those cultural activities

there is development according to corresponding features only, bringing about the manifestation of the tendencies

within the mento-emotional energy.

jāti deśa kāla vyavahitānām api ānantaryaṁ smṛti saṁskārayoḥ ekarūpatvāt

Even though circumstances are separated

by status, location and time,

still the impressions which form cultural activities

and the resulting memories, are of one form

and operate on a timeful sequence.

tāsām anāditvaṁ ca āśiṣaḥ nityatvāt

Those memories and impressions are primeval,

without a beginning.

The hope and desire energies are eternal as well.

hetu phala āśraya ālambanaiḥ saṅgṛhītatvāt

eṣām abhāve tad abhāvaḥ

They exist by what holds them together

in terms of cause and effect, supportive base and lifting influence. Otherwise if their causes are not there,

they have no existence whatsoever.

atīta anāgataṁ svarūpataḥ

asti adhvabhedāt dharmāṇām

There is a true form of the past and future,

which is denoted by the different courses of their characteristics.

te vyakta sūkṣmāḥ guṇātmānaḥ

They are gross or subtle, all depending on their inherent nature.

pariṇāma ekatvāt vastutattvam

The actual composition of an object

is based on the uniqueness of the transformation.

vastusāmye cittabhedāt tayoḥ vibhaktaḥ panthāḥ

Because of a difference

in the mento-emotional energy of two persons,

separate prejudices manifest

in their viewing of the very same object.

na ca ekacitta tantraṁ ced vastu

tat apramāṇakaṁ tadā kiṁ syāt

An object is not dependent

on one person’s mento-emotional perception.

Otherwise, what would happen

if it were not being perceived by that person?

taduparāga apekṣitvāt cittasya vastu jñāta ajñātam

An object is known or unknown,

all depending on the mood and expectation

of the particular mento-emotional energy of the person

in reference to it.

sadā jñātāḥ cittavṛttayaḥ tatprabhoḥ

puruṣasya apariṇāmitvāt

The operations of the mento-emotional energy

are always known to that governor

because of the changelessness of that spirit.

na tat svābhāsaṁ dṛśyatvāt

That mento-emotional energy is not self-illuminative

for it is rather only capable of being perceived.

ekasamaye ca ubhaya anavadhāraṇam

It cannot execute the focus of both at the same time.

cittāntaradṛśye buddhibuddheḥ

atiprasaṅgaḥ smṛtisaṅkaraḥ ca

In the perception of mento-emotional energy

by another such energy,

there would be an intellect

perceiving another intellect independently.

That would cause absurdity and confusion of memory.

citeḥ apratisaṁkramāyāḥ tadākārāpattau svabuddhisaṁvedanam

The perception of its own intellect occurs

when it assumes that form in which there is no movement

from one operation to another.

draṣṭṛ dṛśya uparaktaṁ cittaṁ sarvārtham

The mento-emotional energy which is prejudiced by the perceiver and the perceived, is all evaluating.

tat asaṅkhyeya vāsanābhiḥ citram

api parārthaṁ saṁhatyakāritvāt

Although the mento-emotional energy is diverse

by innumerable subtle impressions,

it acts for the sake of another power

because of its proximity to that other force.

viśeṣadarśinaḥ ātmabhāva bhāvanānivṛttiḥ

There is total stopping

of the operations of mento-emotional energy

for the person who perceives the distinction

between feelings and the spirit itself.

tadā hi vivekanimnaṁ kaivalya prāgbhāraṁ cittam

Then, indeed,

the mento-emotional force is inclined towards discrimination

and gravitates towards the total separation

from the mundane psychology.

tat cchidreṣu pratyayāntarāṇi saṁskārebhyaḥ

Besides that, in the relaxation of the focus,

other mind contents arise in the intervals.

These are based on subtle impressions.

hānam eṣāṁ kleśavat uktam

As authoritatively stated, the complete removal of these

is like the elimination of the mento-emotional afflictions.

prasaṁkhyāne api akusīdasya sarvathā

vivekakhyāteḥ dharmameghaḥ samādhiḥ

For one who sees no gains in material nature,

even while perceiving it in abstract meditation,

he has the super discrimination.

He attained the continuous effortless linkage of the attention

to higher reality which is described

as knowing the mento-emotional clouds of energy

which compel a person to perform

according to nature’s way of acting for beneficial results.

tataḥ kleśa karma nivṛttiḥ

Subsequently there is stoppage of the operation

of the mento-emotional energy

in terms of generation of cultural activities

and their resulting afflictions.

tadā sarva āvaraṇa malāpetasya

jñānasya ānantyāt jñeyam alpam

Then, because of the removal of all mental darkness

and psychological impurities,

that which can be known through the mento-emotional energy, seems trivial in comparison to the unlimited knowledge available when separated from it.

tataḥ kṛtārthānāṁ pariṇāmakrama samāptir guṇānām

Thus, the subtle material nature, having fulfilled its purpose,

its progressive alterations end.

kṣaṇa pratiyogī pariṇāma

aparānta nirgrāhyaḥ kramaḥ

The process, of which moments are a counterpart,

and which causes the alterations,

comes to an end and is clearly perceived.

puruṣārtha śūnyānāṁ guṇānāṁ

pratiprasavaḥ kaivalyaṁ

svarūpapratiṣṭhā vā citiśaktiḥ iti

Separation of the spirit

from the mento-emotional energy (kaivalyam)

occurs when there is neutrality

in respect to the influence of material nature,

when the yogi’s psyche becomes devoid

of the general aims of a human being.

Thus at last, the spirit is established in its own form

as the force empowering the mento-emotional energy.

miércoles, 30 de julio de 2014

lunes, 28 de julio de 2014

domingo, 27 de julio de 2014

the nine distractions for the mind (Patanjali)

Obstacles are to be expected: There are a number of predictable obstacles (1.30) that arise on the inner journey, along with several consequences (1.31) that grow out of them. While these can be a challenge, there is a certain comfort in knowing that they are a natural, predictable part of the process. Knowing this can help to maintain the faith and conviction that were previously discussed as essential (1.20).

One-pointedness is the solution: There is a single, underlying principle that is the antidote for these obstacles and their consequences, and that is the one-pointedness of mind (1.32). Although there are many forms in which this one-pointedness can be practiced, the principle is uniform. If the mind is focused, then it is far less likely to get entangled and lost in the mire of delusion that can come from these obstacles (1.4).

Remember one truth or object: Repeatedly remember one aspect of truth, or one object (1.32). It may be any object, including one of the several that are suggested in the coming sutras (1.33-1.39). It may be related to your religion, an aspect of your own being, a principle, or some other pleasing object. It may be a mantra, short prayer, or affirmation. While there is great breadth of choice in objects, a sincere aspirant will choose wisely the object for this practice, possibly along with the guidance of someone familiar with these practices.

| Predictable Obstacles (1.30) | |||

| Illness | Dullness | Doubt | |

| Negligence | Laziness | Cravings | |

| Misperceptions | Failure | Instability | |

Companions to those Obstacles (1.31) | |||

| Mental and physical pain | Sadness and frustration | ||

| Unsteadiness of the body | Irregular breath | ||

Remember one truth or object: Repeatedly remember one aspect of truth, or one object (1.32). It may be any object, including one of the several that are suggested in the coming sutras (1.33-1.39). It may be related to your religion, an aspect of your own being, a principle, or some other pleasing object. It may be a mantra, short prayer, or affirmation. While there is great breadth of choice in objects, a sincere aspirant will choose wisely the object for this practice, possibly along with the guidance of someone familiar with these practices.

viernes, 25 de julio de 2014

viernes, 18 de julio de 2014

martes, 1 de julio de 2014

PATANJALI—PHILOSOPHER AND YOGIN Georg Feuerstein

Most yogins, like most ordinary people, do not have an intellectual bent. But yogins, unlike

ordinary people, turn this into an advantage by cultivating wisdom and the kind of psychic and

spiritual experiences that the rational mind tends to deny and prevent. And yet there always have been

those Yoga practitioners who were brilliant intellectuals as well. Thus, Shankara of the eighth century

C.E. is not only remembered as the greatest proponent of Hindu nondualist metaphysics, or Advaita

Vedânta, but also as a great adept of Yoga. The Buddhist teacher Nâgârjuna, who lived in the second

century C.E., was not only a celebrated Tantric alchemist and thaumaturgist (siddha) but also a

philosophical genius of the first order. In the sixteenth century C.E., Vijnâna Bhikshu wrote profound

commentaries on all the major schools of thought. He was a noted thinker who greatly impressed the

German pioneering indologist and founder of comparative mythology Max Muller. At the same time

he was a spiritual practitioner of the first order, following Vedântic Jnâna-Yoga.

Similarly, Patanjali, the author or compiler of the Yoga- Sûtra, was obviously a Yoga adept who

also had a great head on his shoulders. As Yoga researcher Christopher Chappie wrote:

Some have said that Patanjali has made no specific philosophical contribution in his presentation

of the yoga school. To the contrary, I suggest that his is a masterful contribution communicated

through nonjudgmentally presenting diverse practices, a methodology deeply rooted in the

culture and traditions of India.1

The Yoga of Patanjali represents the climax of a long development of yogic technology. Of all the

numerous schools that existed in the opening centuries of the Common Era, Patanjali’s school was the

one to become acknowledged as the authoritative system (darshana) of the Yoga tradition. There are

numerous parallels between Patanjali’s Yoga and Buddhism, and it is unknown whether these are

simply due to the synchronous development of Hindu and Buddhist Yoga or are the result of a special

interest in Buddhist teachings on the part of Patanjali. If Patanjali lived in the second century C.E., as

is proposed here, he may well have been exposed to the considerable influence of Buddhism at that

time. But perhaps both explanations apply.

Disappointingly, we know next to nothing about Patanjali. Hindu tradition identifies him with the

famous grammarian of the same name who lived in the second century B.C.E. and authored the Mahâ-

Bhâshya. The consensus of scholarly opinion, however, considers this unlikely. Both the contents and

the terminology of the Yoga-Sûtra suggest the second century C.E. as a probable date for Patanjali,

whoever he may have been.3

In addition to the grammarian, India knows of several other Patanjalis. The name is mentioned as a

clan (gotra) name of the Vedic priest Âsurâyana. The old Shata-Pata-Brâhmana mentions a Patancala

Kâpya, whom the nineteenth-century German scholar Albrecht Weber wrongly tried to connect with

Patanjali.4 Then there was a Sâmkhya teacher by this name whose views are mentioned in the Yukti-

Dîpikâ (late seventh or early eighth century C.E.). Possibly another Patanjali is credited with the

Yoga-Darpana (“Mirror of Yoga”), a manuscript of unknown date. Finally, there was a Yoga teacher

Patanjali who was part of the South Indian Shaiva tradition. His name may be referred to in the title of

Umâpati Shivâcârya’s fourteenth-century Pâtanjala- Sûtra, which is a work on liturgy at the Natarâja

temple of Cidambaram.

Hindu tradition has it that Patanjali was an incarnation of Ananta, or Shesha, the thousand-headed

ruler of the serpent race that is thought to guard the hidden treasures of the earth. The name Patanjali

is said to have been given to Ananta because he desired to teach Yoga on Earth and fell (pat) from

Heaven onto the palm (anjali) of a virtuous woman, named Gonikâ. Iconography often depicts Ananta

as the couch on which God Vishnu reclines. The serpent lord’s many heads symbolize infinity or

omnipresence. Ananta’s connection to Yoga is not difficult to uncover, since Yoga is the secret

treasure, or esoteric lore, par excellence. To this day, many yogins bow to Ananta before they begin

then- daily round of yogic exercises.

serpent lord, Ahîsha, is saluted as follows:

May He who rules to favor the world in many ways by giving up His original [unmanifest] form

—He who is beautifully coiled and many-mouthed, endowed with lethal poisons and yet

removing the host of afflictions (klesha), who is the source of all wisdom (jnâna), and whose

circle of attendant serpents constantly generates pleasure, who is the divine Lord of Serpents:

May He, the bestower of Yoga, yoked in Yoga, protect you with His pure white body.

Whatever we can say about Patanjali is purely speculative. It is reasonable to assume that he was a

great Yoga authority and most probably the head of a school in which study (svâdhyâya) was regarded

as an important aspect of spiritual practice. In composing his aphorisms (sûtra) he availed himself of

existing works. His own philosophical contribution, as far as it can be gauged from the Yoga-Sûtra

itself, was modest. He appears to have been a compiler and systematizer rather than an originator. It is

of course possible that he has written other works that have not survived.

Hiranyagarbha

Western Yoga enthusiasts often regard Patanjali as the father of Yoga, but this is misleading.

According to post-classical traditions, the originator of Yoga was Hiranyagarbha. Although some texts

speak of Hiranyagarbha as a Self-realized adept who lived in ancient times, this notion is doubtful.

The name means “Golden Germ” and in Vedânta cosmomythology refers to the womb of creation, to

the first being to emerge from the unmanifest ground of the world and the matrix of all the myriad

forms of creation. Thus, Hiranyagarbha is a primal cosmic force rather than an individual. To speak of

him—or it—as the originator of Yoga makes sense when one understands that Yoga essentially

consists in altered states of awareness through which the yogin tunes into nonordinary levels of

reality. In this sense, then, Yoga is always revelation. Hiranyagarbha is simply a symbol for the

power, or grace, by which the spiritual process is initiated and revealed.

Later Yoga commentators believed that there was an actual person called Hiranyagarbha who had

authored a treatise on Yoga. Such a work is indeed referred to by many other authorities, but this does

not necessarily say anything about Hiranyagarbha. The most detailed information about that scripture

is found in the twelfth chapter of the Ahirbudhnya-Samhitâ (“Collection of the Dragon of the Deep”),

which is a work of the medieval Vaishnava tradition. According to this scripture, Hiranyagarbha

composed two works on Yoga, one on nirodha-yoga (“Yoga of restriction”) and one on karma-yoga

(“Yoga of action”). The former apparently dealt with the higher stages of the spiritual process, notably

ecstatic states, whereas the latter is said to have been concerned with spiritual attitudes and forms of

behavior.

There may well have been a work on Yoga of this nature, and if it did exist, it might even have

antedated Patanjali’s compilation. In any case, Hiranyagarbha’s work is not remembered to have been

a Sûtra, though it is quite possible that other Sûtras on Yoga existed prior to Patanjali’s composition.

It is a fact, however, that Patanjali’s Yoga-Sûtra has eclipsed all earlier Sûtra works within the Yoga

tradition, perhaps because it was the most comprehensive or systematic.

THE CODIFICATION OF WISDOM—THE YOGA-SÛTRA

Patanjali gave the Yoga tradition its classical format, and hence his school is often referred to as

Classical Yoga. He composed his aphoristic work in the heyday of philosophical speculation and

debate in India, and it is to his credit that he supplied the Yoga tradition with a reasonably

homogeneous theoretical framework that could stand up against the many rival traditions, such as

Vedânta, Nyâya, and not least Buddhism. His composition is in principle a systematic treatise

concerned with defining the most important elements of Yoga theory and practice. Patanjali’s school

was at one time enormously influential, as can be deduced from the many references to the Yoga-

Sûtra, as well as the criticisms of it, in the scriptures of other philosophical systems.

Each school of Hinduism has produced its own Sûtra, with the Sanskrit word sûtra meaning literally

“thread.” A Sûtra composition consists of aphoristic statements that together furnish the reader with a

thread which strings together all the memorable ideas characteristic of that school of thought. A sûtra,

then, is a mnemonic device, rather like a knot in one’s handkerchief or a scribbled note in one’s diary

or appointment book. Just how concise the sûtra style of writing is can be gauged from the following

opening aphorisms of Patanjali’s scripture:

1.1: atha yogânushâsanam (atha yoga-anushâsanam) “Now [commences] the exposition of Yoga.”

1.2: yogashcittavrittinirodhah (yogash citta-vritti- nirodhah)

“Yoga is the restriction of the whirls of consciousness.”

1.3: tadâ drashthuh svarûpe’ vasthânam (tada drashthuh sva-rûpe’ vasthânam)

“Then [i.e., when that restriction has been accomplished] the ‘Seer’ [i.e., the transcendental Self]

appears.”

Of course, such terms as citta (consciousness), vritti (lit. “whirl”), and drashtri (“seer”) are

themselves highly condensed expressions for rather complex concepts. Even such a seemingly

straightforward word as atha (“now”), which opens most traditional Sanskrit treatises, is packed with

meanings, as is evident from the many pages of exegesis dedicated to it in some of the commentaries

on the Yoga-Sûtra.

In his monumental History of Indian Philosophy, Surendranath Dâsgupta made the following

observations about this style of writing:

The systematic treatises were written in short and pregnant half-sentences (sûtras) which did not

elaborate the subject in detail, but served only to hold before the reader the lost threads of

memory of elaborate disquisitions with which he was already thoroughly acquainted. It seems,

therefore, that these pithy half-sentences were like lecture hints, intended for those who had

direct elaborate oral instructions on the subject. It is indeed difficult to guess from the sutras the

extent of their significance, or how far the discussions which they gave rise to in later days were

originally intended by them Our knowledge of Pâtanjala-Yoga is primarily, though not entirely, based on the Yoga-Sûtra. As we

will see, many commentaries have been written on it that aid our understanding of this system. As

scholarship has demonstrated, however, these secondary works do not appear to have come forth from

Patanjali’s school itself, and therefore their expositions need to be taken with a good measure of

discrimination.

Turning to the Yoga-Sûtra itself, we find that it consists of 195 aphorisms or sutras, though some

editions have 196. A number of variant readings are known, but these are generally insignificant and

do not change the meaning of Patanjali’s work. The aphorisms are distributed over four chapters as

follows:

1. samâdhi-pâda, chapter on ecstasy

— 51 aphorisms

2. sâdhanâ-pâda, chapter on the path

— 55 aphorisms

3. vibhûti-pâda, chapter on the powers

— 55 aphorisms

4. kaivalya-pâda, chapter on liberation

— 34 aphorisms

This division is somewhat arbitrary and appears to be the result of an inadequate reediting of the

text. A close study of the Yoga-Sûtra shows that in its present form it cannot possibly be considered an

entirely uniform creation. For this reason various scholars have attempted to reconstruct the original

by dissecting the available text into several subtexts of supposedly independent origins. These efforts,

however, have not been very successful, because they leave us with inconclusive fragments. It is,

therefore, preferable to take a more generous view of Patanjali’s work and grant the possibility that it

is far more homogenous than Western scholarship has tended to assume.

As I have shown in my own detailed examination of the Yoga-Sûtra, this great scripture could well

be a composite of only two distinct Yoga lineages. On the one hand there is the Yoga of eight limbs or

ashta-anga- yoga (written ashtângayoga), and on the other, there is the Yoga of Action ( kriyâ-yoga). I

have suggested that the section dealing with the eight constituent practices may even be a quotation

rather than a later interpolation. If this were indeed correct, the widespread equation of Classical Yoga

with the eightfold path would be a historical curiosity, since the bulk of the Yoga-Sûtra deals with

kriyâ-yoga. But textual reconstructions of this kind are always tentative, and we must keep an open

mind about this as about so many other aspects of Yoga and Yoga history.

The advantage of the kind of methodological approach to the study of the Yoga-Sûtra that I have

proposed is that it presumes the text’s homogeneity or “textual innocence” and thus does not do a

priori violence to the text, as is the case with those textual analyses that set out to prove that a text is

in fact corrupt or composed of fragments and interpolations. At any rate, these scholarly quibbles do

not detract from the merit of the work as it is extant today. Now, as then, the Yoga practitioner can

benefit greatly from the study of Patanjali’s compilation.

viernes, 27 de junio de 2014

lunes, 23 de junio de 2014

Yoga Sutras, Patanjali. Chapter 3: Vibhūti Pāda

deśa bandhaḥ cittasya dhāraṇā

Linking of the attention to a concentration force or person,

involves a restricted location in the mento-emotional energy.

tatra pratyayaḥ ekatānatā dhyānam

When in that location, there is one continuous threadlike flow

of one’s instinctive interest that is the effortless linking

of the attention to a higher concentration force or person.

tadeva arthamātranirbhāsaṁ

svarūpaśūnyam iva samādhiḥ

That same effortless linkage of the attention when experienced

as illumination of the higher concentration force or person,

while the yogi feels as if devoid of himself,

is samādhi or continuous effortless linkage of his attention

to the special person, object, or force.

trayam ekatra saṁyamaḥ

The three as one practice is the complete restraint.

tajjayāt prajñālokaḥ

From the mastery of that complete restraint

of the mento-emotional energy,

one develops the illuminating insight.

tasya bhūmiṣu viniyogaḥ

The practice of this complete restraint occurs in stages.

trayam antaraṅgaṁ pūrvebhyaḥ

In reference to the preliminary stages of yoga,

these three higher states concern the psychological organs.

tadapi bahiraṅgaṁ nirbījasya

But even that initial mastership

of the three higher stages of yoga,

is external in reference to meditation,

which is not motivated by the mento-emotional energy.

abhibhava prādurbhāvau nirodhakṣaṇa

cittānvayaḥ nirodhapariṇāmaḥ

When the connection

with the mento-emotional energy momentarily ceases

during the manifestation and disappearance phases

when there is expression or suppression of the impressions,

that is the restraint of the transforming mento-emotional energy.

tasya praśāntavāhita saṁskārāt

Concerning this practice of restraint,

the impressions derived cause a flow of spiritual peace.

sarvārthatā ekāgratayoḥ kṣaya udayau

cittasya samādhipariṇāmaḥ

The decrease of varying objectives

in the mento-emotional energy

and the increase of the one aspect within it,

is the change noticed

in the practice of continuous effortless linking of the attention

to higher concentration forces, objects or persons.

tataḥ punaḥśānta uditau tulya pratyayaḥu

cittasya ekāgratāpariṇāmaḥ

Then again, when the mind’s content is the same as it was

when it is subsiding and when it is emerging,

that is the transformation called

“having one aspect in front of, or before the attention”.

etena bhūtendriyeṣu dharma lakṣaṇa avasthā

pariṇāmāḥ vyākhyātāḥ

By this description of the changes, quality and shape,

the changing conditions of the various states of matter,

as well as of the sensual energy, was described.

śānta udita avyapadeśya dharma anupātī dharmī

When the collapsed, emergent and latent forces

reach full retrogression, that is the most basic condition.

karma anyatvaṁ pariṇāma anyatve hetuḥ

The cause of a difference in the transformation

is the difference in the sequential changes.

pariṇāmatraya saṁyamāt atīta anāgatajñānam

From the complete restrain of the mento-emotional energy

in terms of the three-fold transformations within it,

the yogi gets information about the past and future.

śabda artha pratyayānām itaretarādhyāsāt

saṅkaraḥ tatpravibhāga saṁyamāt

sarvabhūta rutajñānam

From the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

In relation to mental clarity,

regarding the intermixture resulting from the superimposition

one for the other, of sound, its meaning and the related mentality, knowledge about the language of all creatures is gained.

saṁskāra sākṣātkaraṇāt pūrvajātijñānam

From direct intuitive perception of the subtle impressions

stored in the memory, the yogi gains knowledge of previous lives.

pratyayasya paracittajñānam

A yogi can know the contents

of the mental and emotional energy

in the mind of others.

na ca tat sālambanaṁ tasya aviṣayī bhūtatvāt

And he does not check a factor

which is the support of that content,

for it is not the actual object in question.

kāya rūpa saṁyamāt tadgrāhyaśakti

stambhe cakṣuḥ prakāśa asaṁprayoge 'ntardhānam

From the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy in relation to the shape of the body, on the suspension of the receptive energy,

there is no contact between light and vision, which results in invisibility.

etena śabdādi antardhānam uktam

By this method,

sound and the related sensual pursuits, may be restrained, which results in the related non -perceptibility.

sopakramaṁ nirupakramaṁ ca karma

tatsaṁyamāt aparāntajñānam ariṣṭebhyaḥ vā

Complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

in relation to current and destined cultural activities

results in knowledge of entry into the hereafter.

Or the same result is gained

by the complete restraint in relation to portents.

maitryādiṣu balāni

By complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

in relation to friendliness, he develops that very same power.

baleṣu hasti balādīni

By complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

in relation to strength,

the yogin acquires strength of an elephant.

The same applies to other aspects.

pravṛitti āloka nyāsāt sūkṣma

vyavahita viprakṛṣṭajñānam

From the application of supernatural insight

to the force producing cultural activities,

a yogi gets information about what is subtle, concealed

and what is remote from him.

bhuvanajñānaṁ sūrye saṁyamāt

From the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

in relation to the sun god or the sun planet,

knowledge of the solar system is gained.

candre tārāvyūhajñānam

By complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy,

in reference to the moon or moon-god,

the yogi gets knowledge about the system of stars.

dhruve tadgatijñānam

By the complete restrain of the mento-emotional energy

in relation to the Pole Star,

a yogi can know of the course of planets and stars.

nābhicakre kāyavyūhajñānam

By complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

in relation to the focusing on the navel energy-gyrating center,

the yogi gets knowledge about the layout of his body.

kaṇṭhakūpe kṣutpipāsā nivṛttiḥ

By the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

in focusing on the gullet,

a yogi causes the suppression of hunger and thirst.

kūrmanāḍyāṃ sthairyam

By the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

in focusing on the kurmanadi subtle nerve,

a yogi acquires steadiness of his psyche.

mūrdhajyotiṣi siddhadarśanam

By the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

as it is focused on the shining light in the head of the subtle body,

a yogi gets views of the perfected beings.

prātibhāt vā sarvam

By complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy,

while focusing on the shining organ of divination

in the head of the subtle body,

the yogin gets the ability to know all reality.

hṛdaye cittasaṁvit

By the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

as it is focused on the causal body in the vicinity of the chest,

the yogi gets thorough insight

into the cause of the mental and emotional energy.

sattva puruṣayoḥ atyantāsaṁkīrṇayoḥ

pratyayaḥ aviśeṣaḥ bhogaḥ parārthatvāt

svārthasaṁyamāt puruṣajñānam

Experience results from the inability to distinguish

between the individual spirit

and the intelligence energy of material nature,

even though they are very distinct.

By complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

while focusing on self-interest distinct from the other interest,

a yogi gets knowledge of the individual spirit.

tataḥ prātibha śrāvaṇa vedana

ādarśa āsvāda vārtāḥ jāyante

From that focus is produced smelling, tasting, seeing,

touching and hearing, through the shining organ of divination.

te samādhau upasargāḥ vyutthāne siddhayaḥ

Those divination skills are obstacles

in the practice of continuous effortless linkage of the attention

to a higher concentration force, object or person.

But in expressing,

they are considered as mystic perfectional skills.

bandhakāraṇa śaithilyāt pracāra

saṁvedanāt ca cittasya paraśarīrāveśaḥ

The entrance into another body is possible

by slackening the cause of bondage

and by knowing the channels of the mento-emotional energy.

udānajayāt jala paṅka kaṇṭakādiṣu asaṇgaḥ utkrāntiḥ ca

By mastery over the air

which rises from the throat into the head,

a yogi can rise over or not have contact

with water, mud or sharp objects.

samānajayāt jvalanam

By conquest of the samana digestive force,

a yogi’s psyche blazes or shines with a fiery glow.

śrotra ākāśayoḥ saṁbandha saṁyamāt divyaṁ śrotram

By the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy,

while focusing on the hearing sense and space,

a yogin develops supernatural and divine hearing.

kāya ākāśayoḥ saṁbandha saṁyamāt

laghutūlasamāpatteḥ ca ākāśagamanam

By the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy,

while linking the mind

to the relationship between the body and the sky

and linking the attention to being as light as cotton fluff,

a yogi acquires the ability to pass through the atmosphere.

bahiḥ akalpitā vṛttiḥ mahāvidehā tataḥ

prakāśa āvaraṇakṣayaḥ

By the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy

which is external, which is not formed,

a yogi achieves the great bodiless state.

From that the great mental darkness which veils the light,

is dissipated.

sthūla svarūpa sūkṣma anvaya arthavatva

saṁyamāt bhūtajayaḥ

By the complete restraint of the mento-emotional energy,

while linking the attention to the gross forms, real nature,

subtle distribution and value of states of matter,

a yogi gets conquest over them.

tataḥ aṇimādi prādurbhāvaḥ kāyasaṁpat

taddharma anabhighātaḥ ca

From minuteness and other related mystic skills

come the perfection of the subtle body

and the non-obstructions of its functions.

rūpa lāvaṇya bala vajra saṁhananatvāni kāyasaṁpat

Beautiful form, charm, mystic force, diamond-like definition

come from the perfection of the subtle body.

grahaṇa svarūpa asmitā anvaya arthavattva

saṁyamāt indriyajayaḥ

From the continuous effortless linkage of the attention

to sensual grasping, to the form of the sensual energy,

to its identifying powers, to its connection instinct

and to its actual worth,

a yogi acquires conquest over his relationship with it.

tataḥ manojavitvaṁ vikaraṇabhāvaḥ pradhānajayaḥ ca

Subsequently, there is conquest

over the influence of subtle matter

and over the parting away or dispersion

of the mento-emotional energy,

with the required swiftness of mind.

sattva puruṣa anyatā khyātimātrasya

sarvabhāva adhiṣṭhātṛtvaṁ sarvajñātṛtvaṁ ca

Only when there is distinct discrimination

between the clarifying perception of material nature

and the spiritual personality,

does the yogi attain complete disaffection

and all-applicative intuition.

tadvairāgyāt api doṣabījakṣaye kaivalyam

By a lack of interest, even to that

(discrimination between the clarifying mundane energy

and the self) when the cause of that defect is eliminated,

the absolute isolation of the self from the lower psyche of itself,

is achieved.

sthānyupanimantraṇe saṅgasmayākaraṇaṁ

punaraniṣṭa prasaṅgāt

On being invited by a person

from the place one would attain if his body died,

a yogi should be non-responsive, not desiring their association

and not being fascinated,

otherwise that would cause unwanted features of existence

to arise again.

kṣaṇa tatkramayoḥ saṁyamāt vivekajaṁ jñānam

By the continuous effortless linkage of the attention

to the moment and to the sequence of the moments,

the yogi has knowledge caused by the subtle discrimination.

jāti lakṣaṇa deśaiḥ anyatā anavacchedāt

tulyayoḥ tataḥ pratipattiḥ

Subsequently, the yogi has perception of two similar realties

which otherwise could not be sorted

due to a lack of definition in terms of their general category, individual characteristic and location.

tārakaṁ sarvaviṣayaṁ sarvathāviṣayaṁ

akramaṁ ca iti vivekajaṁ jñānam

The distinction caused by subtle discrimination

is the crossing over or transcending

of all subtle and gross mundane objects

in all ways they are presented,

without the yogi taking recourse

to any other sequential perceptions of mind reliance.

sattva puruṣayoḥ śuddhi sāmye kaivalyam iti

When there is equal purity between the intelligence energy

of material nature and the spirit,

then there is total separation

from the mundane psychology.

sábado, 7 de junio de 2014

kaivalya ligth on life BKS Iyengar

“The realized yogi continues to function and act in the world, but in a way that is free. He is free from desires of motivation and free from the fruit or rewards of action. The yogi is utterly disinterested but paradoxically full of the engagement of compassion. He is in the world but of it.”

B.K.S Iyengar

martes, 27 de mayo de 2014

Shiva, la carrera de un dios, A.Van Lysebeth 2/2

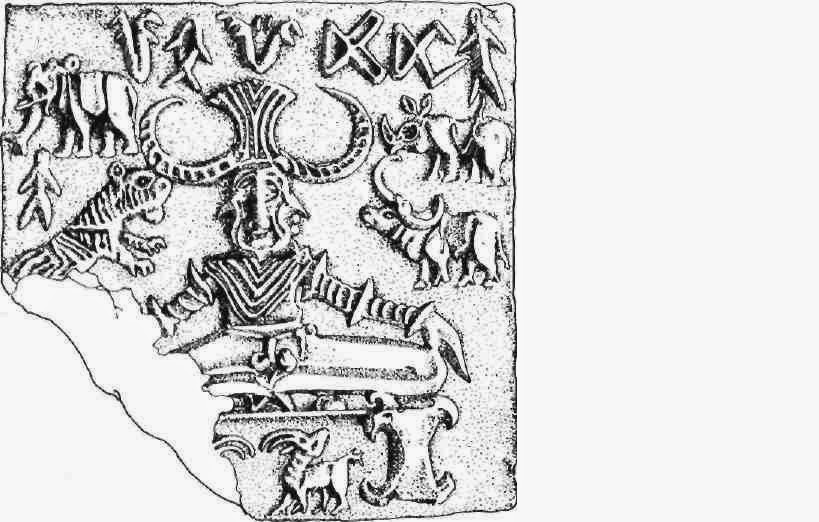

Descifremos la danza de Shiva

Entre las variantes de la danza de Shiva, la más conocida en el sur de la India es la Nadanta,